Get your ticket to DUTCH Fest 2026! Join us March 12-14 in Dallas, TX for cutting-edge hormone education and hands-on learning. Learn more and register today.*

*DUTCH Fest is exclusive to registered DUTCH Providers. Only registered DUTCH Providers can attend.

Cardiovascular Health and the DUTCH Test

Rebecca Clemson, ND

February is American Heart Month, a time to focus on cardiovascular health and disease prevention. Even with advances in medical technology and medications, cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be the leading cause of death for both men and women worldwide. Supporting optimal cardiovascular health is achievable by addressing (or hopefully preventing) modifiable CVD risk factors.

The development of CVD is multifactorial in nature, with major risks including:

- Inflammation/oxidative stress

- Insulin resistance and diabetes

- Abnormal lipid levels

- Stress

- Genetics

- Aging

- Obesity

- Lifestyle (including nutritional deficiencies and lack of exercise)

While often overlooked, hormones play an integral role in cardiovascular health. Understanding this relationship is an important aspect of cardiovascular health assessment. The DUTCH test provides insights into key hormones that affect cardiovascular health and function including estrogen, testosterone, and cortisol.

Sex Hormones and Cardiovascular Health

Estrogen, in particular estradiol, is an important player in supporting a healthy cardiovascular system in both men and women. The heart and vasculature tissue are rich in estrogen receptors. Estrogen supports healthy endothelial function by promoting elasticity, vasodilation, healthy lipid levels, and modulating inflammation1. Together these help to maintain healthy blood pressure and decrease the risk of atherosclerosis. Estradiol modulates inflammation by both inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines and stimulating anti-inflammatory cytokines1. It also increases antioxidant status by regulating antioxidant enzyme activity2. Additionally, estradiol supports blood glucose levels and insulin sensitivity. In these ways estradiol helps to modulate many of the risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease. Deficiency in estrogen can increase the risk for CVD in men and women alike.

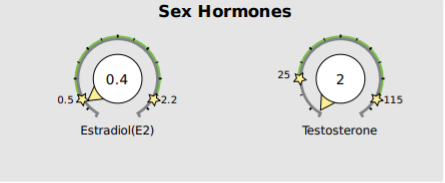

Low estrogens in a postmenopausal female

Because estrogen has such a positive effect on cardiovascular health, many women are at lower risk of cardiovascular disease compared to men until the menopausal transition period. The menopausal transition, especially late perimenopause, is a critical period during which CVD risk accelerates. Late perimenopause is associated with a rapid decline in endothelial function that worsens with prolonged estradiol deficiency. This period is associated with increased vascular aging4. This is a key period to focus on cardiovascular health and working to decrease risk factors associated with CVD. Currently menopausal hormone replacement therapy (MHRT) is not approved for the prevention or treatment of CVD; however, data suggests that estradiol replacement can potentially improve CVD outcomes. Women who start HRT earlier may see greater cardiovascular benefits. For more about MHRT and cardiovascular disease risk see our article here.

Low estradiol and testosterone in a 70-year-old male

Although the relationship between testosterone and cardiovascular health requires further research, evidence suggests that testosterone also has a protective effect on the cardiovascular system, especially in men. Similar to estradiol, testosterone supports cardiovascular health in men by promoting healthy endothelial function and blood pressure, modulating inflammation, supporting insulin sensitivity and decreasing diabetes risk, maintaining a healthy lipid profile, and supporting healthy body composition – maintaining lean muscle mass while decreasing visceral adiposity5 . Low testosterone levels in men are associated with increased CVD risk including hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke. Improving testosterone levels may decrease these adverse cardiovascular events5.

HPA Axis Function and Cardiovascular Health

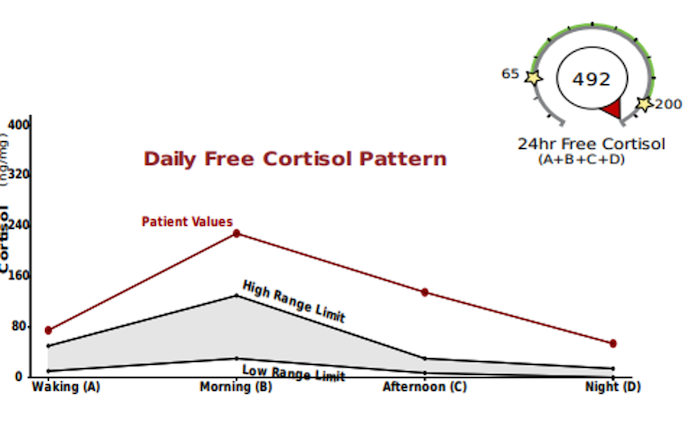

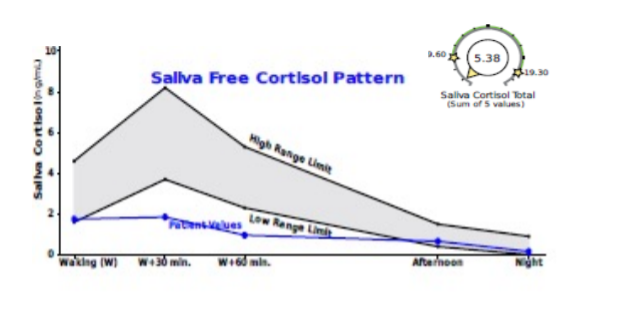

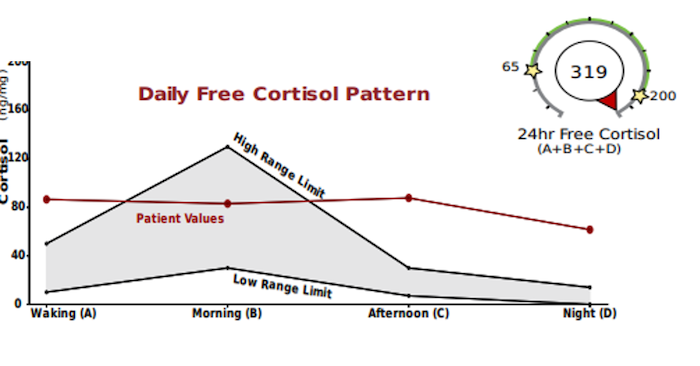

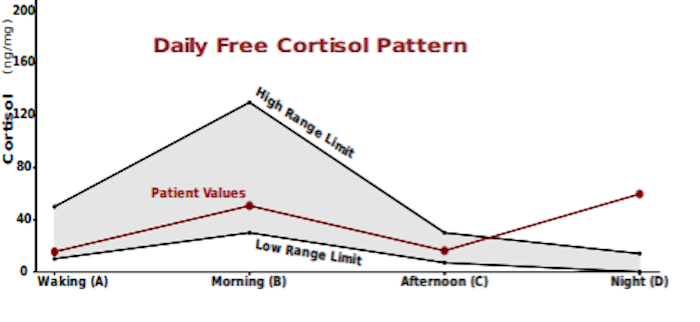

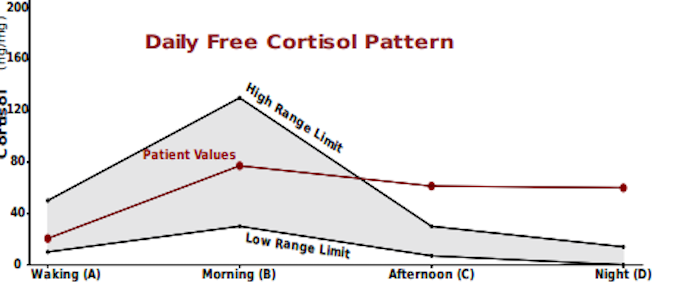

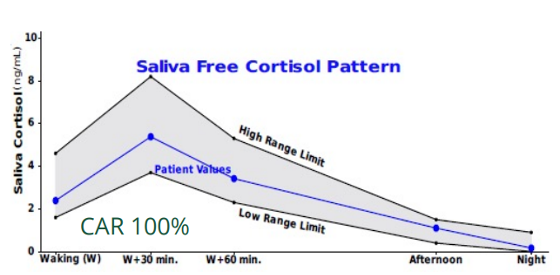

Chronic stress is a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease6. Studies have found high levels of cortisol are associated with hypertension, insulin resistance, blood sugar dysregulation, and obesity – all major risk factors for CVD9. Cortisol is a key player in several important body systems: Blood sugar management, insulin sensitivity, the circadian clock (sleep/wake cycle), immune function, inflammation, and regulation of blood pressure and electrolyte balance through its effects on the sympathetic nervous system and kidney function (and more). These actions affect almost every organ system and tissue, including multiple effects on the cardiovascular system. Healthy cortisol has a striking surge in the morning with a slow decline throughout the rest of the day. When this is impaired, flat, or inverted (high at night), studies show the development of the same impacts of chronic stress as listed above, whether total cortisol is elevated or not. Studies have shown that disruptions in the diurnal cortisol rhythm are associated with increased CVD risk and mortality8-14.

There are several cortisol patterns to be aware of when assessing CVD risk. Patterns associated with increased cardiovascular disease include the following.

High Cortisol Levels:

The Flat Cortisol Curve: an absent diurnal rhythm. Whether the cortisol production was low or high, little variability in output is seen throughout the day. Associated with increased overall mortality, CVD, inflammation, and obesity8-12.

High Nighttime Cortisol: Increased levels of late-night cortisol are also a predictor of higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and stroke11.

The Decreased Slope: Associated with increased coronary artery disease 10, adipocyte hypertrophy/ increased adipose tissue and hyperinsulinemia9.

There is also a cortisol pattern associated with decreased CVD risk. A more pronounced cortisol response with a greater diurnal cortisol peak-to-bedtime ratio is associated with lower risk of CV mortality and of stroke11.

Estradiol, testosterone, and cortisol play an important role in cardiovascular health and function, which is well represented in research. Beyond these hormones, the DUTCH test also includes additional markers that can help assess for potential risks to cardiovascular health such as inflammation and oxidative stress. These include markers of estrogen, testosterone, and cortisol metabolism, and the organic acid panel.

Summary

Sex hormones play an important role in maintaining cardiovascular health. They support healthy endothelial function, modulate inflammation and increase antioxidant activity, optimize lipid levels, and mitigate risks factors associated with CVD including insulin resistance and diabetes.

Sex hormone deficiencies, specifically estradiol and testosterone, are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

For women, the menopausal transition, especially late perimenopause, is a critical period during which CVD risk accelerates. This is an important timeframe to support cardiovascular health with lifestyle optimization, and some women may benefit from menopausal hormone therapy.

Healthy HPA axis function is important for cardiovascular health. High cortisol levels and dysregulated cortisol curves are associated with increased risk of CVD, stroke, and mortality.

DUTCH testing can help to assess for sex hormone deficiencies and HPA axis dysfunction. Additional markers can give insights into inflammation and oxidative stress. Learn more about using the DUTCH Test in your practice by becoming a DUTCH Provider.

Additional Resources:

- Stress and Cortisol in a Hypertensive Patient

- American Heart Month: 6 Tips for Managing Stress & Improving Cardiovascular Health

- Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment: How the DUTCH Test Applies

- In Pursuit of Best Practice: Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT)

- Men's Health: The Focus on Healthspan and Lifespan for Men

- Connecting the Dots Between Cardiovascular Disease, Inflammation & Hormones

References

- Lira-Silva E, Del Valle Mondragón L, Pérez-Torres I, et al. Possible implication of estrogenic compounds on heart disease in menopausal women. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162:114649. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114649

- Gubbels Bupp MR, Potluri T, Fink AL, Klein SL. The Confluence of Sex Hormones and Aging on Immunity. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1269. Published 2018 Jun 4. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01269

- Bellanti F, Matteo M, Rollo T, et al. Sex hormones modulate circulating antioxidant enzymes: impact of estrogen therapy. Redox Biol. 2013;1(1):340-346. Published 2013 Jun 19. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2013.05.003

- Moreau KL, Hildreth KL, Meditz AL, Deane KD, Kohrt WM. Endothelial function is impaired across the stages of the menopause transition in healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(12):4692-4700. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-2244

- Moreau KL, Babcock MC, Hildreth KL. Sex differences in vascular aging in response to testosterone. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):18. Published 2020 Apr 15. doi:10.1186/s13293-020-00294-8

- Babcock MC, DuBose LE, Witten TL, et al. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Are Associated With Age-Related Endothelial Dysfunction in Men With Low Testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(2):e500-e514. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab715

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937-952. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9

- Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, McQuillan MT, Dahlke KA, Gilbert KE. Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;83:25-41. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.018 – references flat cortisol curve and CVD risk

- Ortiz R, Kluwe B, Lazarus S, Teruel MN, Joseph JJ. Cortisol and cardiometabolic disease: a target for advancing health equity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022;33(11):786-797. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2022.08.002

- Matthews K, Schwartz J, Cohen S, Seeman T. Diurnal cortisol decline is related to coronary calcification: CARDIA study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(5):657-661. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000244071.42939.0e

- Karl S, Johar H, Ladwig KH, Peters A, Lederbogen F. Dysregulated diurnal cortisol patterns are associated with cardiovascular mortality: findings from the KORA-F3 study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022;141:105753. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105753

- Imami L, Jiang Y, Murdock KW, Zilioli S. Links between socioeconomic status, daily depressive affect, diurnal cortisol patterns, and all-cause mortality. Psychosom Med. 2022;84(1):29-39. doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000001004

- Mohd Azmi NAS, Juliana N, Azmani S, et al. Cortisol on Circadian Rhythm and Its Effect on Cardiovascular System. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):676. Published 2021 Jan 14. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020676

- Ronaldson A, Kidd T, Poole L, Leigh E, Jahangiri M, Steptoe A. Diurnal Cor

TAGS

General Health

General Hormone Health

Men's Health

Women's Health

Cardiovascular Disease

HPA Axis

Cortisol Awakening Response

Cortisol

Estrogen