Decoding the HPA Axis: How Stress, Cortisol & Circadian Rhythms Shape Our Health

Tom Guilliams, PhD

Listen wherever you get your podcasts

Never miss an episode! Subscribe to our podcast on your favorite platform. If you haven’t subscribed yet, please do so and stay updated with our latest content.

Episode 82

Published November 26, 2024

In this episode, Tom Guilliams and Dr. Jaclyn Smeaton delve into the complexities of the HPA axis, exploring its role in stress response, metabolic regulation, and overall health. They discuss the multifaceted nature of cortisol, its impact on glucose levels, and how early life stressors can shape HPA axis function.

This episode also explores:

- The significance of perceived stress

- How circadian rhythm influences HPA axis function

- The intricate connections between obesity, inflammation, and the HPA axis

- Holistic approaches to managing HPA axis dysfunction, including the use of adaptogens and the importance of physical activity

- Gender differences in stress response and the factors that contribute to burnout

Key Moments

00:00 Understanding the HPA Axis: A Comprehensive Overview

05:49 The Impact of Early Life Stress on HPA Axis

11:49 Circadian Rhythms and HPA Axis Function

22:09 Glycemic Dysregulation: The Chicken and Egg Dilemma

34:27 The Connection Between Obesity and Inflammation

42:01 Holistic Approaches to HPA Axis Dysfunction

47:10 The Role of Adaptogens in Stress Management

52:36 Physical Activity as an Adaptogen

Transcript

Jaclyn (00:02.008)

So I'm so excited to get some time to talk with you, Tom, about the HPA axis, because you are one of the people that I've learned from, from reading your textbooks. And I'm really, really excited about today. So thank you so much for joining us.

Tom Guilliams (00:15.421)

Well, you know, I'm always excited to talk about the HPA axis, any parts of it, any anything. So, yeah, I'm glad to be here again.

Jaclyn (00:25.112)

Well, I think just for listeners, we're gonna be like zooming in and zooming out in a way that you probably haven't done before. So I would just encourage you to listen in to the end because I think you're gonna get a lot out of the day today. But for people who are listening who are maybe newer to understanding the HPA access, can you start by just telling us a little bit about what it does and why we have it physiologically?

Tom Guilliams (00:46.653)

Yeah, so I think, I mean, I think most everybody kind of thinks of the HPA axis, the hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis for those who need that part. That we think of it typically we orient ourselves as part of the stress response. So we always probably most everybody learns it as part of the stress response. And we assume that if something is stressful in our life, the brain, the hypothalamus, you know, senses that stress of some kind, and then tells the pituitary to make a signal that eventually tells the adrenal gland to make cortisol. So, and then cortisol goes around and does all of what it does to rebalance or bring us back to where we need to be as far as homeostasis. And then of course, the other part of that is the is cortisol then tells the brain that shut off cortisol. So it sort of has this feedback loop. So that's really the basic idea. I think people orient themselves mostly from the stress response. And so we can get into a little more of the detail there. What I've been thinking about mostly is the HPA axis really should be thought of as I think one of our previous conversations was on sort of like this whole metabolic regulator, that it really isn't for stress. It is for everything. And stress is a an immediate need. And so of course, the HPA axis steps up, it's it, you know, takes over the the capacity to recalibrate wherever the stressor is, but it really is robbing from its normal metabolic pathways, normal metabolic machinery, and signaling capacity, and also the circadian, the circadian factor that's there. So all of those things really you know, I remember when I, when I wrote my first book on HPA axis and I happened to run into my old college professor, immunology professor actually, but he also teaches human physiology and I hadn't seen him in years and years. And he said, you wrote something on the HPA axis and on cortisol, he says, that that's a glucose regulating system. And it, you know, he didn't, he didn't really even view it as a stress response system. He viewed it as a glucose regulating system, which I think is

Jaclyn (02:55.064)

Mmm.

Tom Guilliams (03:03.029)

is a, I mean, that's why we call cortisol a glucocorticoid because it manages glucose. So again, I think one of the things I've learned about teaching the HPA axis, mostly to clinicians, is that every layer, it keeps expanding. And oftentimes clinicians, unfortunately, have a somewhat simplistic version of what the HPA axis does. And then there's so much more that it actually does than we think.

Jaclyn (03:29.046)

That's super true. think we think of it as a simple like fight or flight light switch activity when we first start to learn about HPA axis function. And clearly that's like understating the importance of cortisol as a hormone. So you mentioned that it has these activities to like regulate. Can you give us a couple of biological examples where cortisol steps into like in a hopeful world, temporarily change physiological function, to like bring back to homeostasis.

Tom Guilliams (04:00.275)

Well, I think that if we go back to glucose, that's probably the most dynamic because in fact, you know, the gold standard for stressing the HPA axis is actually doing a clamp where you basically give somebody insulin and you drop their blood glucose and you will immediately see a jump in CRH, ACTH and then cortisol. It'll be very quick because it's going to then start the process of. Releasing more glucose into the bloodstream. And so there's a couple different ways it does that. Obviously, it up regulates the gluconeogenesis, but also it becomes a signal for insulin resistance. So you don't want your, you know, you don't want your liver or your fat cells or even, you know, those cells to be sucking up all your glucose. So you're going to make them insensitive to insulin. And so you can get more glucose to the bloodstream, to the brain, to other parts of the body that actually need it for survival.

You know those things can deal with it later. So you have that that factor I think in a sort of an immediate sort of thing Obviously, there are other factors like in inflammatory signals, which we can talk about later. So cortisol becomes a steroid anti-inflammatory

And so it's able to then adjust the immune system. But again, all of these things, we might say have collateral damage. So the collateral damage of releasing glucose is insulin resistance, which is fine if you need it for the next two hours. But if you're using, obviously, your HPA axis to release glucose on a regular basis, you become insulin resistant long term. Same thing here. If you want to reduce inflammation, that can be a great

Tom Guilliams (05:49.483)

great thing if you need it in a localized area, but it also suppresses lot of immune function. And by suppressing all these immune functions over a long period of time, you get immunosuppression and the kinds of things that you'd get, the vulnerabilities you'd get for that. all of these sort of immediate benefits, almost all of them come with some sort of chronic collateral damage if they're not localized and short term.

Jaclyn (06:15.488)

It's so fascinating because when you think about like the obesity crisis and type 2 metabolic, know, type 2 diabetes and just metabolic dysfunction in the country, when you describe how cortisol kind of interplays with that, it really adds another layer that we need to be managing as clinicians because it's not possibly not all about poor diet.

Tom Guilliams (06:38.649)

yeah. I mean, I think we've talked about this in the past, obviously, as adults, we can say, okay, I know what's stressing me out, you know, what's my work, it's my schedule, it's whatever these things are that that we normally put as lifestyle events that sort of are, quote unquote, stress. But there's all of these other factors, including early life stress, early life stressors that change the HPA axis in such a way that it kind of creates a posture towards poor stress responders. And that also comes typically with metabolic dysregulation. So we often see early life obesity, other metabolic syndrome, inflammatory conditions, these kinds of things. And a lot of that can be traced back to stressors that are cortisol related at probably, know, prepuberty time period, even intrauterine, if you want to go that far back, that actually changed the signal capacity of the HPA axis.

Jaclyn (07:40.163)

Mm-hmm.

Jaclyn (07:44.268)

Yeah, that's an area of interest for me and it's fascinating because I mean, I do so much preconception work. There's some interesting studies on moms who have high stress or, you know, whatever those stressors are. And they look at HPA axis dysregulation, which now they know there's like epigenetic connections that are heritable to the offspring that impact the offspring's long-term health. But they've even looked at things like using SSRIs in pregnancy to manage anxiety, which actually has

It does, the mother reports feeling better on the SSRI, but there is no improvement in the offspring. They still inherit the HPA access dysfunction and epigenetics of the parent, which is so fascinating and really speaks to the fact that this is something that needs to be worked on at the core and really treated at its core function, which is improving health, reducing stress, and all of the complicated factors that lead into that.

Tom Guilliams (08:29.149)

Yeah. Yeah.

Jaclyn (08:40.302)

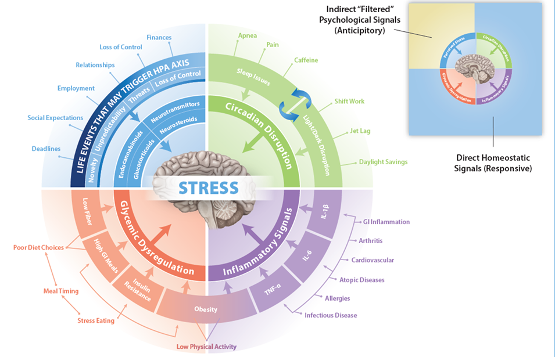

You're kind of leading us into this infographic that you were generous enough to provide ahead of time that we're going link to in the show notes. Because I think this is something that, when I saw it, the first thing I thought was like, wow, if I were describing stress to my patients and wanting them to make changes, I would have this in front of me laminated to show people over and over again. Because it really pulls together a more comprehensive, holistic view of HPA axis function and why maybe just quitting your job might not be enough to really cure you and ultimately fix your HPA access. So, might be a start for some people, not you or I, we're lucky, we get to be in great jobs. So let's start with the area that I think most people do think about, which you started to talk about when it comes to HPA access dysfunction, which is like the emotional, psychological stressor. So let's talk a little bit more about what that is. We can start with maybe the, you talked about like,

Tom Guilliams (09:13.703)

It might be a start for some people. Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Jaclyn (09:37.868)

the adverse childhood experiences like A score. We know A score plays a big role in people's long-term health and probably related through the HPA access function. Maybe let's start there and then talk about the day-to-day experiences of stress that we have.

Tom Guilliams (09:52.691)

Yeah, so I mean, as I started thinking about and I worked with a lot of different people over the years and trying to define sort of what causes the brain, what defines stress for the brain, specifically the hypothalamus and

there are these, you know, direct homeo, what would I call homeostatic signals? These are responsive and we can talk about those later. And the one you're, you're concentrating on here is what are, what we might call anticipatory or psychosocial signals. Okay. So in the, in the research world, they often call this perceived stress because, in some people it's going to be, it literally is the perception of an event that's occurring in your life.

So those can be you know, obviously we think of when you if you did a man on the street interview, and you said, Are you stressed? And if somebody says yes, and you ask them what what is stressing you, they're likely going to say something about their finances, something about their relationship, something about their, you their boss or the deadlines or some expectations they have from their social environments or something like that, and they are perceiving that event and they are responding to it in what they would refer to as a stressful way. So these are all these sorts of perceived events that are anticipatory. Your brain is attempting to change its metabolism, thinking that it's going to encounter some event. That is perceiving as it's going to change my physiology. Okay, so even though, you know, we often say we often talk about like running from a tiger or these kinds of things. And most of the idea if you think about going back to your first question, why do we have the stress response? Why is it metabolic? Because it's assuming that there's going to be a metabolic dysregulation caused by a stressor. So that's how it it's geared up. It's geared up for a metabolic event. Well,

Tom Guilliams (11:49.671)

know, getting a call from your, from your financial advisor telling you that you're, you know, in debt or something that you didn't know about or you're being sued is not a metabolic event, but it your body's gearing up for it to be a metabolic event. So it does all those same sorts of things. So when the researchers started looking into this, they tried to say, well, what is, what is the ultimate definer of those events? And essentially, you know, they came up with this acronym, nuts and NUTS okay so I didn't invent that but it's n stands for novelty. Yeah, n stands for novelty, so anything new anything that's new that comes down you immediately have to think about that it's a perceived stress. It's unpredictable that's the you and you unpredictable so you you're not able to know exactly what's going to happen. So you immediately begin thinking of a stressor. The T stands for a threat.

Jaclyn (12:24.332)

You should have, it's a good one.

Tom Guilliams (12:46.811)

So it's either a threat to your physical body. Obviously, maybe if you see somebody coming, coming to you with a baseball bat, but also the idea of threat to your ego or threat to your sense of wellbeing. And then the last is a, and this is where the acronym kind of breaks down. It's a sense of a loss of control. So the S is sort of a little bit more general there, but so anything that's new, anything that's unpredictable, anything that you feel is threatening, but ultimately this idea of loss of control is probably a better definition of the whole thing. Because if you look at the perceived stress questionnaires, which are validated, and there's a 10 and a 14 question, and I think there's even a shorter one, like a seven question one. If you're a clinician, you should know these, you should have these, you can go online, find them, they're all downloadable in like, I don't 30 languages. And they basically ask the question to the patient, let's say finances, it's saying, do you feel in control of the finances? Do you feel in control of the relationship that you have here? Or it's all about their their sense of control. Because ultimately, when you when you feel like you're out of control, that's essentially that's what drives the stressor. So if it's something new, and you're you're not in control of how it's going to turn out, you go to, you know, we always talk about the idea of, you know, public speaking.

You don't know, know, are you, it's, it's, you know, a new audience. It's a new, you know, your, your ego is threatened if they don't laugh at your joke, whatever, all those kinds of things are all there. And so it creates this, this stressor. So, you know, there's, there's a way of, of, so I would, you know, using these perceived stress scales, the PSS, use, using these, they will give you a sense of the patient's perception of their stress. And this is validated to salivary cortisol, it's validated to even telomeres and all kinds of other measures of, of, you know, of some biomarker of stress is all tied to perceive stress. Now, that just tells you what their perception of their stress is, you in order to really drill down, is this a relationship? Is this employment? Is this, you know, do they need to their job? Or what is it that they need to do to change?

Tom Guilliams (15:11.647)

That's where you look at life change inventories, where you get a whole list of things and say, what events have happened in your life in the last, usually one year, kind of figure out which of those are maybe driving this. And that's where you need to know the patient's history. You need to know a little more about them than just what their salivary cortisol or their urinary cortisol would be at that moment.

Jaclyn (15:37.686)

It's interesting when you talk about that because it's really a hopeful conversation when I hear you talk about that because it seems like perception of like sense of control is modifiable regardless of someone's circumstances, right? So what that says to me is like, are not a, you know, and we see this play out because we all have patients and friends and family where you could have two people going through hardship, the same exact hardship, and they have a different perception of the situation or a different level of stress around the situation. And that is a modifiable, teachable behavioral piece. Is that what we talk about when we talk about resilience in the HPA axis? Is resilience gaining a better ability to manage that sense of loss of control?

Tom Guilliams (16:32.139)

Well, there's a I think there's a couple layers of resilience, one would be probably just the history of the stressor. So obviously, how much how resilient how, how fluid or how, how plastic is probably the right kind of the more scientific way we talk about how plastic is the stress response to a new stressor. And you can sort of measure that perhaps by, you know, doing some of these physiological tests or something like that. But I think what you're maybe getting at is learned responses, coping, being able to cope, being able to perceive an event, because like I said, it's a perception. So the same exact event, public speaking or even on the family.

My wife is a hospice nurse. And so she obviously is going into situations that can be very stressful for family members. And there's a wide range of ways that the siblings or the, know, brothers and sisters of the person that's dying, you know, are going through that grief. And so some of them, based on probably learned responses and other sorts of things, are handling it quite differently than others. And so it's the exact same event.

But because of the relationship they have or their history of other things going on. And so teaching people, teaching children how to handle stressful situations. I mean, we've all been in employment situations where somebody doesn't handle a situation and you wonder, you know, how did that happen? How did they, you know, blow up or

However, that happened. And it's, you know, probably some learned responses or some lack of learned responses in those individuals that affect everyone else. So I think that's part of the plasticity. I think like you said, you know, the the community that you're in, the group of people that you surround yourself with in those times of crises or other things, I think will will change your perception.

Tom Guilliams (18:31.313)

And so that's, know, a lot of times when you're counseling people in stressful situation, you can't change the event, but you can certainly put it in context and allow them to change the perception of that event. And that will decrease the stress that they have.

Jaclyn (18:46.53)

Yeah, I'm finding this so fascinating because it also gets me thinking about people who have like over anticipation of something that's not even happened or that may not even be likely to happen, but it feels threatening even before it happens. And that you'd imagine that would cause the same HPA access stimulation just through that anticipation. Yeah.

Tom Guilliams (19:05.043)

Right, right. And I think if you look at the infographic, and this, where it talks about lifestyle events, you'll see that, you know, where you have this novelty unpredictability, but then you have a set of arrows that goes to another series of more, I would say, biological components. And so your brain

Jaclyn (19:21.43)

Yeah, let's talk about those.

Tom Guilliams (19:26.631)

has to take an event and it has to then interpret it chemically into something. And so the way that the brain does that, the way the hypothalamus does that is it takes, it can change the sensitivity of each of the receptors, the components in the brain. these can be changed, the sensitivity of these can be changed by neurotransmitters. So serotonin, GABA, those kinds of things, neuro steroids. So your brain actually makes not cortisol, at least that we don't know yet that makes cortisol, but like a pregnenolone and there's other allopregnanolone, there's a few others, but DHEA is also there. And so your endocannabinoids, we talk about the whole cannabinoid system that's there. And then of course, there are some glucocorticoids signaling the feedback inhibition.

In some people that have anxiety or depression or changes in neurotransmitters or changes in neuro steroids, they will again see a perceived event as being more anxious or maybe more depressing, or it won't create the same signals in those individuals or they will over-respond because of these other sorts of signals. So some of this can be, let's say it's chemistry or biochemistry, not just sort of it's all in your head kind of thing. So you have the ability to filter this through this system of receptors and enzymes and things like that. And that's why some people are, let's say, up more for perceiving things more anxiously or more depressed or.

And we see a hyper responsiveness of the HPA axis. Even in men versus women, there's differences in different sorts of stressors that are likely due to hormones or maybe something that we don't know of yet. So it's, again, there's this biochemical filter that.

Tom Guilliams (21:24.081)

It's one of the reasons why, you know, getting somebody's neurotransmitters or understanding how that works, maybe the guts involved, there's a lot of other things going involved, involved the neurotransmitters, why that's not just straightforward that every event is the same.

Jaclyn (21:38.84)

So interesting. So let's move on to another quadrant in your diagram, which is circadian disruption. Now, we talk a lot about the importance of light and dark and kind of this juxtaposition of melatonin and vitamin D. And we are starting to talk more about the impact of sleep and the impact of circadian rhythm generally in health. And this seems to be a really important reason why. Can you talk a little bit about that circadian disruption and how that affects the HPA axis?

Tom Guilliams (22:09.181)

Yeah, so I think, I think circadian rhythm in general needs to be, you know, more at the foundation of I would say functional integrative medicine, really all medicine or health. But I think as far as understanding its importance, because probably and I mean, it's anybody's guess, but almost half of the genes that are expressed on any given day have some sort of circadian rhythm to them. It might even be more than that. And so, you know, we talk about turning genes on and turning genes off and we, you know, we talk about this quite a bit. We talk about genetics, like you just mentioned epigenetics, but the circadian, I, know, something that is circadian tells you that there's intended to be sort of a rhythm of the day and all these genes should be firing at a given time during the day to make everything work. And when that doesn't happen, there's this inefficiency, the metabolic inefficiency throughout all of really almost every system in the body. And of course, of course, this turns out to affect other rhythms that are circadian, like you know, the menstrual cycle and other cycles, hormonal cycles.

And so as it turns out, the cortisol rhythm, the reason that everybody who measures cortisol knows that your cortisol is highest in the morning and then it kind of goes down until it's lowest sort of in the middle of the night. Part of that part of the reason that is, is because cortisol is one of the main circadian signals to tell, you know, all of these clocks that are not in the brain, but out in the in the peripheral tissue, tell it basically what time is it, you know, it's time to wake up, it's time it's cortisol is at its peak. And, of course, that's triggered to light hitting the the optic nerve. And so it's recalibrating sort of all the systems based on on

Tom Guilliams (24:07.779)

on you know, light hitting the hypothalamus hypothalamus then telling cortisol to produce on a circadian rhythm, and then all the cells then know what time it is. And so anytime you have somebody whose light day cycle is completely shifting,

Let's say jet lags classic example of that. But even daylight savings, which we just had a few weeks ago, you know, this was a fall back. So actually, it, you know, it extends our normal clock is a little longer than 24 hours. So going backwards is easier than going forward. If you remember spring forward is always much harder. But jet lag, people that do shift work where they're working on nights and then on the weekends, they try to live, you know, a normal life with their family and they're sleeping during night again, these kind of things, they completely change the signal, which is trying to synchronize itself with metabolic signals. So the metabolic signals will be like eating and daylight activity. So if you're if you're eating during the day,

Jaclyn (25:11.075)

Hmm.

Tom Guilliams (25:15.485)

And you're active during the day and you're sleeping at night, you create this strong rhythm of on and off on and off. But if you go eight hours, let's say you go to Europe or you go to Asia. Now all of a sudden you're trying to eat during the day, but your clock is still unsynchronized with the light. And so all of these metabolic, of everybody knows you feel really horrible. Your whole body like, why do I feel like everything's off? Because everything is off. and what it's doing is then the HPA axis is sensing this as a major stressor and it's trying to resynchronize everything as quickly as possible. And this is where, you know, trying to help yourself out, maybe trying to trigger like melatonin at the right time, trying to make sure you stay active in the morning when sunlight is at the location that you've arrived at, you know, trying to get sleep during darkness. You can, you you can probably get that usually within

They usually say it takes like a day per hour of shift is kind of what they often say, but you can speed that up by really, really paying attention to what you're doing. But this is something that people do every week to themselves. I mean, how many people, know, work?

Jaclyn (26:13.026)

Hmm.

Tom Guilliams (26:25.567)

They have to go from 6 a.m. in the morning and then all of sudden on Friday they want to stay out till, you know, two in the morning and then they try to get enough sleep and then Monday they hit some again. And so we're really kind of forcing our HPA axis to fix this sometimes on a weekly basis. And that again, drains the reserve capacity of our stress response system.

Jaclyn (26:46.67)

So does sleep trouble cause the same disruption like insomnia, sleep apnea, things like that? Do we see the same type of HPA axis stimulation or disruption?

Tom Guilliams (26:57.459)

Yeah, so if you look at it's not always the same in every individual. But if you look at like sleep apnea is one of the classics they've done. They've looked at for those who do the the cortisol awakening response, they'll they'll show that people with sleep apnea typically have a flattened cortisol awakening response. They don't, they're not getting whatever it takes to get a good off signal. They're not getting that full jump in the morning. So it tells you that they're the plasticity of the HP

And so in some of the studies, what they do, obviously, they put people on, know, CPAP or other things to help with their sleeping. And as they sleep better, sure enough, they get more of a robust cortisol, a waking response. So you're, you're basically creating the signals needed for the HPA axis to respond. So I don't know if it's the same for, every component, like sleep, you know, delayed sleep onset versus waking after sleep.

I would not be surprised if every one of those creates some sort of HP access response, which is probably discernible even with cortisol, like a diurnal cortisol with CAR.

Jaclyn (28:11.106)

Yeah, I wish we could like test all new parents as our kids get older and we start to sleep, you don't sleep for a while, then you start to sleep again and all those changes that can affect us.

Tom Guilliams (28:18.867)

Yeah.

And all the decisions that you need to make during that time period aren't always the best either because as you know, high cortisol levels then create, you know, poor executive memory, poor executive decision making, those kinds of things.

Jaclyn (28:33.814)

Absolutely. So let's move into the third quadrant of kind of things that affect or stimulate HPA axis dysfunction, which is glycemic dysregulation. And I think this is gonna be a really hot topic. I'm really excited to talk more about this because this seems a little bit like a chicken and an egg type of problem where glycemic dysregulation is a perceived stressor by the brain. But then also when you get HPA axis dysfunction, like you've shared with us, it causes further...glycemic dysregulation and metabolic dysregulation. So where do you want to even start with this category?

Tom Guilliams (29:07.967)

Well, I mean, let's go back to the idea that cortisol is a glucocorticoid. So it is designed to manage this. so glycemic dysregulation, hypoglycemia, so low blood sugar, is the most emergency. Of all these, it's the most immediate emergency situation. So that's why it's so robust in affecting the HPA axis. And so you have that response.

But ironically,

There's something called the Trier Social Stress Test. This is where people get up in front of a group of people that try to stress them out and they take their salivary cortisol. And they did a study that was really interesting. They found that people who were, this is a psychosocial stressor. So it's just basically putting somebody in a stressful situation in a controlled environment. And they gave people different kinds of foods beforehand. And the people that they gave sugar to that ended up having hyperglycemia, had a higher response to the stressor, meaning they made more cortisol because their body was hypersensitive to the stressor. So what I tell people is hypoglycemia is bad, hyperglycemia, because hypoglycemia triggers the HPA axis, hyperglycemia makes it more sensitive to stress.

And so what do we see when we have these obese individuals who are maybe not controlling their diet very well? We have them going from hypoglycemia to hyperglycemia. They keep bouncing all around. And so you basically are constantly trying to use the HPA axis, which really isn't supposed to be doing this, to try to manage your blood sugar. Because between diet and insulin,

Tom Guilliams (30:56.573)

you can't do it because these cells are becoming insulin resistant, the cells of let's say the muscles and the adipocytes. So it is kind of like a chicken and egg, it's sort of like a spiral that can continue to get out of control further and further. And, you know, the only way around that is to intervene some other way. So, you know, diet, other things that you can do to improve insulin sensitivity. You know, if you look in the if you look at the idea of

Jaclyn (31:16.93)

Mm-hmm.

Tom Guilliams (31:25.459)

poor dietary choices, people are eating the wrong things, they're eating them at the wrong time. There's actually some data to suggest that this idea of what we call stressful eating, people that are under stress that consume foods that are salty, sweet, and fat. So those are the three kind of consistent things that actually biologically, they actually will reduce cortisol.

So it does have an effect. You crave the things that will work. Obviously, all these are temporary, because they're obviously then going to exacerbate all of these same problems. But physiologically, they do have an effect on the HP access. And so people sort of, if you want to call self-medicate. So yeah, this is sort of a chronic cycle that is very difficult to get out of.

Jaclyn (32:02.061)

Right.

Jaclyn (32:16.214)

It's interesting, you're just making me think about like a personal story. I have a son, he's 12, he's type 1 diabetic. And like one of the only times he's had dangerously low blood sugar, know, emergency response needed. What I first picked up on was anger. It was this intense, like I've never seen it before. It was like a different person, right? And that was it, you know, now making the connection there, that was like that cortisol probably really surging, creating that fight or flight type of attitude as his.

Tom Guilliams (32:35.284)

Wow.

Jaclyn (32:45.024)

insulin was really tanking. I mean, I've just, my point being I've seen that in action and that very strong cortisol surge. It's quite amazing, you know, that we can be responsive.

Tom Guilliams (32:54.559)

Yeah. Well, in the case of hypoglycemia like that, you also have would have an epinephrine spike too. So that that would probably drive a lot of that as well. but yeah, so and then of course, the long term effect of all of this is obesity, which then drives more of the insulin resistance. And of course, then stores cortisol is cortisone. So you have, you know, it kind of exacerbates a lot of these factors, because now you have, you know, a depot of adipose tissue, which then

Jaclyn (33:01.792)

Exactly. Yeah. Yeah.

Tom Guilliams (33:24.803)

you know as well as I do that it affects female hormones and know estrogen testosterone a number of other things are going on there including the storage of cortisol or as cortisol

Jaclyn (33:35.416)

Definitely, and I mean, you know, on Dutch, like Mark is very passionate about telling a more comprehensive HPA axis story as well, which is why we don't just do free cortisol diurnal rhythm. You also get cortisol metabolites and cortisol to cortisone conversion. We can talk more about that and the enzyme systems there if we have time today, but it is critically important and we can absolutely see the patterns on the Dutch test where when a customer calls in, we're able to say, this patient have metabolic dysfunction or obesity? And you can really see

Tom Guilliams (33:53.428)

Yeah.

Jaclyn (34:05.218)

the pattern shift of what happens over time under those conditions. So it's really very visible.

Tom Guilliams (34:08.935)

Yeah. Yeah.

Yeah. So yeah, mean, so yeah, this is a big, I mean, you can't, you can't overestimate, you know, the, the impact of glycemic dysregulation and the fluctuation is really, I think what does the most damage.

Jaclyn (34:27.63)

That makes a lot of sense. And really talking about obesity, it kind of brings us into this crossover area where obesity is also connected. That kind of fourth quadrant you talk about, which is inflammation as a stressor to the HPA axis. Let's talk a bit about that.

Tom Guilliams (34:41.267)

Yeah, so I mean, if you again, if you just look at the core biology of what I usually consider the the triad signals of the inflammation, which is would be TNF alpha, IL six and IL one beta, and obviously there's others, but those are the kind of the the core ones. If you look at just what they do, they have there's receptors in the brain, they will immediately up regulate the HPA axis. Because again, if these are up regulated, the brain is trying to say, there something wrong? Obviously blood sugar is wrong, if circadian rhythm is wrong, or if I'm sensing inflammation, there must be something going on in the immune system that needs to be dealt with. And so those signals can come from anywhere. they're pretty agnostic. mean, whether you have some sort of infectious disease, whether you have even an allergic response or a gut inflammation or arthritis or whatever, maybe a lower level with cardiovascular disease, something like that. All of these would be driving these signals. And so they're going to be driving the HPA axis cortisol is an anti inflammatory. So it is, but it's, mean, we, say it's an anti inflammatory, which it is, but it's an immune suppressing steroid, just like we have with other other steroids. And so it is able to quench some of that inflammation, but it does so at the expense oftentimes of reducing your immune response to other things. And so, you know, one of the classic examples of this is often, you know, people that run marathons or these even longer runs than marathons, the 50 miles, 100 miles. And those people, if you look at them, they will have huge spikes of cortisol, mean, just off the chart high, but they also have immune suppression and the ability, know, usually within the week of doing something like that, they often will come down with some respiratory infection or some other infection.

Tom Guilliams (36:41.881)

And actually, interestingly, they will deplete their gut membrane, so they'll have intestinal permeability. In the research world, if you want to give somebody leaky gut syndrome, you put them in a hot room and you run them on a treadmill long enough, and eventually their immune system will break and they'll have intestinal permeability and their cortisol will spike. So it's kind of all of these things. You can put yourself in a situation where...where you create a vulnerability. And of course, the HPA axis is trying to fix that cortisol to the rescue and other things that it's not the only thing but cortisol is one of the main things here to try to fix that immediate problem.

Jaclyn (37:22.294)

One of the areas of inflammation that you highlight in your graphic is GI inflammation, which I think I'd like to just kind of call out specifically. Obviously, there's a lot that can go on, like atopic conditions, allergies, infections you mentioned. But because this is such an area of interest in functional medicine, I kind of want to double click on it a little bit because so much of our immune system is located around our gut. Can you talk a little bit about what you've seen in literature in your own experience around that GI inflammation piece and how important is it? Are we overemphasizing it in functional medicine?

Tom Guilliams (37:58.343)

I don't probably not. But maybe we don't understand it always completely. In the sense that we assume that the inflammation is going to always be demonstrable in the gut that is we're gonna you know, have IBD or some inflammatory condition that we can measure there. And is it if you really look at some of these like atopic diseases or what we would

Jaclyn (38:00.855)

Okay.

Tom Guilliams (38:21.765)

used to be mostly called autoimmune diseases. A lot of these are auto-inflammatory diseases. So obviously IBD is an auto-inflammatory disease, but so is rheumatoid arthritis for the most part. And so what happens when we think of these, this GI inflammation is...

Jaclyn (38:26.67)

Mm.

Tom Guilliams (38:39.443)

we have some sort of immune response. Let's say it's related to some sort of dysbiotic condition, some sort of intestinal permeability, something that the immune system is seeing as a potential threat. And it immediately shifts to this, what we, if you're familiar with the T helper cell family, now TH1, TH17, which are gonna upregulate inflammatory signals. And so,

And probably one of the components that's triggered there is something called the inflammasome, which got such big play during COVID. But the inflammasome essentially, for the most part, is just a receptor that upregulates the conversion of pre-IL1 beta into the signal, which is IL1 beta. And that also triggers, not surprisingly, TNF alpha and IL6. So again, the triad of those, 17 is involved in that as well. And those signals don't stay in the gut. So their job is to set up the whole immune system in the whole body to say, Hey, we've got an inflammation going on here. And so it these then migrate to other parts of the body. And when they migrate to the joint, they then stimulate some of the destruction of the joint. And we get rheumatoid arthritis. But they also go to the brain.

So the brain sees all of these signals as well. And that's why the HP axis is turned on. so the gut inflammation or maybe you could even say inflammatory signals derived from the gut, because I think that's probably a better way to think about it. It can be an inflammation like IBD, but oftentimes it migrates to other parts of the body, to the skin, to the joints.

Jaclyn (40:18.85)

Mm.

Tom Guilliams (40:29.341)

to the liver. I we have a lot of that going on with, you know, the inflammatory sort of metabolic inflammatory diseases of the liver. So, but because you have such exposure in the gut, the immune system is exposed to more pathogens or more potential pathogens or allergens or immunogenic components. And also this is where the immune system learns how to respond. So if you get a wrong response, that is to say the immune system responds aggressively to a commensal organism because it has a genetic or some sort of bad, you know, some sort of signal that it's inappropriate, then you can have this sort of inappropriate which is one of the things that's thought to drive many of these auto inflammatory conditions like IBD, but some of the others like rheumatoid arthritis. And that's why it's connected to dysbiosis, intestinal permeability and those kinds of things.

Jaclyn (41:23.022)

Mm-hmm.

Jaclyn (41:30.37)

Yeah, I mean, think the connection's becoming pretty strong. Like, when my son was diagnosed with type 1, even in the hospital, the first thing they said is the reason why he has this is likely caused by dysbiosis in the gut, which I was like, wow, you know. Talking to an atropat, they didn't know I was, but I'm like, this is starting to become mainstream. That's pretty amazing.

Tom Guilliams (41:47.411)

Yeah, yeah, I think I think we're gonna learn. I mean, obviously, we're learning a lot of these things. And the issue is, and I think this where we get a lot of pushback is it's not only the one thing, obviously, some people are genetically predisposed. And so these signals drive a signal in one person that's going to amount to, let's say a diagnosable disease, quote unquote, and another person, it's not going to affect them at all. So so it

Jaclyn (41:58.284)

Right. Of course.

Mm-hmm.

Jaclyn (42:10.872)

would be fine. Right.

Tom Guilliams (42:13.927)

I think sometimes it'll get a pushback because it's like, well, dysbiosis didn't cause it all, obviously. right. And so the question is, you know, how do then address it? And that becomes the more difficult thing because, you know, there might be five things you need to address to actually get sort of a change that's statistically significant in a clinical trial or something.

Jaclyn (42:18.663)

No, it's just a contributing factor.

Jaclyn (42:35.542)

Of course. Well, I want to shift gears a little bit and talk about, you know, now that we have this kind of more holistic model for HPA axis stimulation and dysregulation, thinking about inflammation, glycemic dysregulation, circadian rhythm, and then can I call them psychosocial stressors? If we think about that, it gives us a really comprehensive model for addressing HPA axis dysfunction, but also maybe a little bit more challenging of a model because you've really got to figure out what your patient needs.

Thinking from the top, when you think generally about devising a treatment strategy for someone with HPA access regulation, like what's the first thing a clinician should be thinking about?

Tom Guilliams (43:16.383)

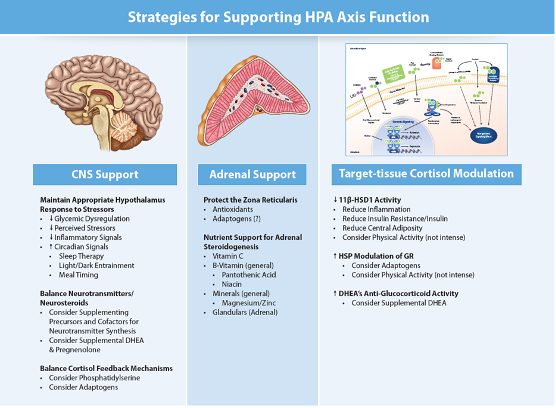

So well, think the first thing they should be asking the question is, I mean, it depends on where they came up with this. So have they done cortisol testing? Have they looked at a complete perceived stress questionnaire and those kinds of things? But usually when I think about this in a more comprehensive way, of course, I've written a lot about this, in the in the old days, we would always think of, you know, supporting the adrenals. And so I think most everybody can go back into the archives and realize why that's a very simplistic approach. But I try to think of sort of three areas. One are what is how do you affect the brain?

How can you affect the way the brain sees its stress? And those are the four things we just mentioned. There are other things, blood pressure, know, blood temperature, you know, there's other factors, but if you can deal with those four things, understanding a person's circadian rhythm, sleep, understanding what's driving inflammation in their body, where they are for glycemic dysregulation, all those responsive areas of the physiology, and then the anticipatory part, perceived stress, most most of your therapies are going to be there, I say probably 90 % of them. And so you want to look at what can I do to support the brain. And those are going to be things like reducing glycemic dysregulation, reducing perceived stressors. So like we talked about, reducing inflammatory signaling and all the circadian things that you can do. And then if you're looking beyond that, and this is where it's a little more tricky, because I don't think we have nearly as we're not refined as well in understanding how to measure and understand modulating neurotransmitters, or neuro steroids, or some of these are even endocannabinoid system. You know, I think we're going to learn a lot more about those in probably the next 10 years. But you know, compared to what we know about sort of the cortisol DHEA response, we know less about that. So there are, you know, things that you can do to maybe to modulate sort of that that biochemistry, but I would say that that's going to be

Jaclyn (45:01.432)

Hmm.

Tom Guilliams (45:24.435)

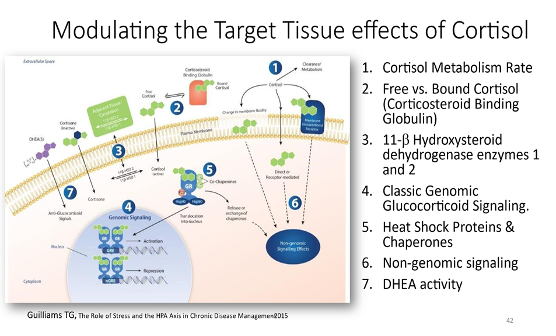

the majority of what a clinician is gonna do. On the other hand, there are what I call modulating target tissue cortisol responses. And that's where, you know, we don't probably have time to get into it right now, but just measuring cortisol tells you a lot, okay? So you can learn a lot about measuring free cortisol and metabolites and ratios and all these kinds of things. And of course, DHEA and DHEA sulfate as well, but then the question becomes, okay, what do I, does every tissue respond to cortisol in the same way? how can I affect the ratio between cortisol, which is the active component and cortisone, or how much, can I modulate the corticosteroid binding globulin? So we talked a lot, I'm sure you talk a lot about, sex hormone binding glibulin and how that when you go up and down with that how it dramatically affects free estrogen things like that free testosterone well the same thing here most cortisol is bound by corticosteroid binding glibulin and albumin and you can up regulate and down regulate corticosteroid binding glibulin you can up regulate and down regulate the enzymes that convert cortisol to cortisone and and guess what a lot of those things are driven by inflammation, insulin sensitivity and central adiposity in general. looking at those kinds of things really does address a lot more issues than people think when you're dealing with that. that's, that's for them. That's what I mostly tell clinicians.

Jaclyn (47:02.765)

Hmm.

Tom Guilliams (47:10.033)

And then I would suggest that most of the things that we do, vitamins, minerals, all of those things that we assume that are helping probably are helping because they increase the reserve capacity to deal with all metabolic functions. And that's where maybe you're getting some benefit with what we might call adrenal support or something like that.

Jaclyn (47:30.21)

Yeah, can you talk a little bit about the ways and mechanisms where adaptogens are helpful? Are they mostly affecting the adrenal glands or does it affect the central nervous system or the target tissue? I know, it's like the angelic mention we'd all love to know.

Tom Guilliams (47:41.607)

So there's a lot written on this. Alexander Pinozian, I think, has done the most work on this, published a lot of data or a lot of information, mostly on the history of use of adaptogens. And for the most part, adaptogens are these herbal, mostly they're herbal products, not, maybe in memory exclusively, but an adaptogen, we the generic term of adaptogen would be something that allows an animal or human to be able to withstand more stress. And so the question is, how does how does that work? And I think there's probably for me, one of the the leading contenders for how these are working are by expanding the expression of chaperones.

And I know we didn't get into this, the details of this, but just if I can briefly go into cortisol does its work by going into the cell, binding to a receptor, the glucocorticoid receptor, and together they migrate into the nucleus and they sit on genes and they turn them on or turn them off. Okay. And so some of the proteins that chaperone or take that receptor into the nucleus, are a family of compounds. And we've learned quite a few, there's quite a few of these that we've now learned about. Some of them are what we call heat shock proteins, which are all chaperones, they help proteins fold. But there's a whole group of other proteins that all bind to the glucocorticoid receptor and bring it in. And by doing that, it affects the stress response.

And so what we've learned is that some of these compounds known that are found in adaptogenic herbs are able to modify upregulate heat shock protein production or some of these other chaperones. And I think that's one of the leading contenders for how something that can be taken sort of generically has such a profound effect on all of these events, including pain, reducing pain, you know,

Tom Guilliams (49:57.915)

helping the stress response, say, rebound faster, these kinds of things. It probably needs to be working at some fundamental level like that. There's some other potentially neurotransmitter effects that adaptogens make and have. We know that if you look at adaptogens outside of the world of stress, what do they do? Many of them are anti inflammatory, many of them are they promote insulin sensitivity. So it's possible that there's other factors. My guess is there's something that we haven't discovered yet that it's gonna sort of blow our brain when it would really find out how some of these adaptogens work. Like I said, most of these are herbs and most of them interestingly are themselves herbs that come from very hostile environments. And they're often the root of that herb because the root, it's not exclusive. There are some that are not the roots, but the root of some of those herbs, it's like some of these are contained of years of concentrating some of these compounds because it's not like the leaf that just falls off at the end of the season. So this is an area that I'm very intrigued with, but I don't, it's sort of a mystery of exactly how it's working. So I think it's probably working at multiple levels.

Jaclyn (51:16.282)

Well, thanks for sharing your thoughts around it. I mean, these are the kinds of things that we can't wait to learn more about because they have implications in so many places and spaces throughout our human physiology that if we can learn to modify, we can probably make a pretty big impact clinically. So very exciting. Well.

Tom Guilliams (51:33.619)

Yeah. And I would just say, I would just say that about some of these, the way they're used traditionally is usually in teas or in, like long-term use. And so in the West, we like try to rescue everything. So we assume we wait till we're very stressed and then I'm going to go get some Ashwagandha or some Sushandra or some ginseng. And I'm just going to dose it as high as I can to reduce my stress. And that's really not how they're used. They're used long-term.

Jaclyn (51:51.394)

Take it for a week.

Tom Guilliams (52:01.417)

little bit everyday kind of thing and I think that's probably the better use of these types of compounds.

Jaclyn (52:08.854)

Yeah, thanks for that feedback. And I really love, I mean, it's kind of trending right now to see adaptogens mixed into foods, like blended into coffee blends or put into drinks like you'd normally drink, like, I don't know, a fizzy drink, fizzy soda replacement in a healthier version. It's exciting to me to see that coming up because not, tea is not everybody's cup of tea. So if you can put the adaptogens into things that people are already using.

Tom Guilliams (52:22.899)

Yeah. Great.

Jaclyn (52:36.052)

in modern day cultures, like it's a really a great way that you could be adding that to the, you know, to our diet essentially, which is how these are used traditionally.

Tom Guilliams (52:44.593)

And one last adaptogen, which we don't often think of, it's maybe one of the most powerful ones, is moderate physical activity. When you are physically active, you will create a modest stress on your tissues, which will then create an adaptive response to the stress. so being sedentary is really harmful, but moderate physical activity on a regular basis is a great adaptogen.

Jaclyn (53:16.354)

I love that you framed it that way. So, yep, let's all go for a walk. Yep, part of the benefits of walking. Well, Tom, thank you so much. It's always amazing to have you on the podcast. And I feel like the luckiest person in the world to get to sit with experts like you and ask questions. And I've learned a lot today. So thanks, Dr. Williams, for joining us.

Tom Guilliams (53:34.761)

Well, thank you for having me. Love talking about this topic.

About our speaker

Tom Guilliams, PhD, serves as an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Pharmacy. For the past two decades, he has spent his time investigating the mechanisms and actions of lifestyle and nutrient-based therapies, and he is an expert in the therapeutic uses of dietary supplements.

Since 2014, he has been writing a series of teaching manuals that outline and evaluate the principles and protocols that are fundamental to the functional and integrative medical community. Tom is also the founder and director of the Point Institute, an independent research and publishing organization that facilitates the distribution of his many publications.

Show Notes

Learn more about Tom Guilliams and his research organization, Point Institute.

Check out other episodes of the DUTCH Podcast with Tom Guilliams: What’s the Deal with the Pregnenolone Steal? and HPA Axis: A Whole-Body Stress Response System.

Become a DUTCH Provider to gain access to free educational resources, expert clinical support, peer-reviewed and validated research, and comprehensive patient reports.

Please Note: The contents of this video are for educational and informational purposes only. The information is not to be interpreted as, or mistaken for, clinical advice. Please consult a medical professional or healthcare provider for medical advice, diagnoses, or treatment.

Disclaimer: Special offer of 50% OFF first five kits is invalid 60 days after new provider registration.

TAGS

Women's Health

Men's Health

Cortisol

Cortisol Metabolism

HPA Axis

Stress

General Hormone Health

Unlock Hormone Insights

If you enjoyed our podcast, why not take the next step? Sign up as a DUTCH provider and gain access to exclusive resources and professional support—all for free!

Benefits of Being a DUTCH Provider

- Mastering Functional Hormone Testing: access to a complete five-part online training course at your own pace

- 50% off first five kits (invalid 60 days after new provider registration)

- One-on-one clinical support

- Supportive provider onboarding

- All-new functional medicine resources

- Group mentorship sessions

- DUTCH Interpretive Guide

- DUTCH Practitioner’s Resource