YES! Urine testing can be used to monitor transdermal estrogen creams or gels

Mark Newman, MS

YES! Urine testing can be used to monitor transdermal estrogen creams or gels

by Mark Newman, MS

In this blog, you will see the data that has led us to the following conclusions about monitoring transdermal estrogen:

- Serum and urine (DUTCH) testing can be used to monitor transdermal creams and gels.

- Clinical parameters tested in the research (bone loss, vasomotor symptoms, FSH suppression) parallel urine and serum results, not saliva.

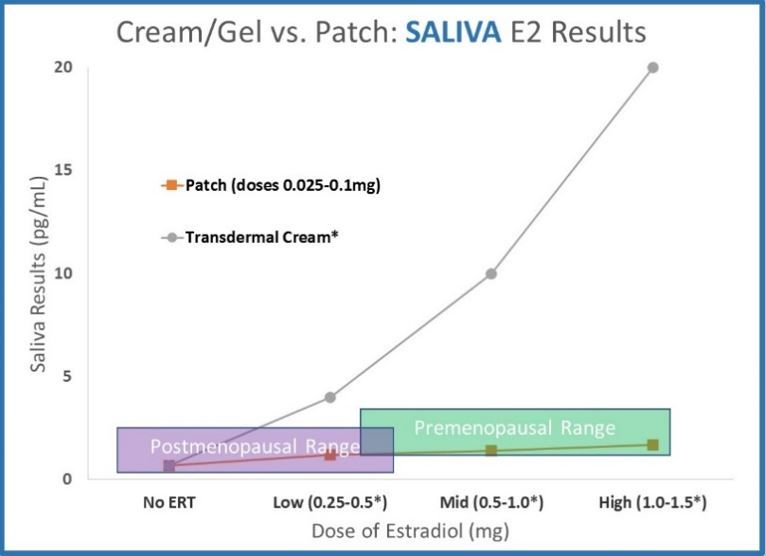

- Salivary estradiol results following transdermal creams/gels are elevated dramatically and lack clinical utility.

- Estradiol doses of 0.25-1.0mg result in improved bone density, vasomotor symptoms, and serum or DUTCH results lifted out of the postmenopausal range thru the bottom part of the premenopausal range.

NOTE: This blog post is educational and not an endorsement for a particular HRT dose or route of administration.

There has long been confusion about how to best monitor estrogen creams and gels. We have shared in this confusion, but the data has now made the situation much clearer. First, let’s establish what we know about a less confusing, but related delivery system, transdermal patches:

- In women who use estrogen patches, serum, urine and saliva values move from below the premenopausal range to within the premenopausal range in a dose-dependent manner, moving from no supplementation up through the higher doses used (0.1mg).

- This FDA study data shows that all estrogen-patch doses (even the very lowest – 0.025mg) help to relieve vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes) and increase bone density. This is important! We will show later that 0.5-1.5mg doses of creams or gels work similarly.

Now, let’s see how the same data is presented when we switch the delivery to a transdermal gel or cream:

- Serum and urine results behave similarly after treatment with a gel or cream compared to a transdermal patch. As therapy increases (from none to 1.5mg), serum and urine values increase in a dose-dependent manner from postmenopausal levels to within (or very near) premenopausal levels. Urine data is essentially equivalent for gels and creams and comes from more than 1,300 patients taking these products and completing the DUTCH test. The serum data for transdermal gel is from the data provided to the FDA from the makers of Divigel.

- The FDA data does not list the reference ranges for the specific method used for the serum data. We chose Lab Corp ranges to display the FDA data relative to expected ranges. The serum data for patches is slightly higher compared to gels. The two studies likely used different analytical methods (notice the results of women not on therapy is slightly higher for patches. Given that they are from different studies, the results compare favorably.

Commonly used transdermal creams and gels result in similar concentrations compared to commonly used doses of estradiol patches. This is true in both serum and urine; however, salivary testing tells a VERY different story.

- Saliva data for transdermal creams and gels dramatically deviates from serum and urine. Results increase far above premenopausal levels with relatively small doses. The data shown (ZRT data published online, 2012 for testing 12 hours after application) shows results far above premenopausal levels.

WHAT CLINICAL MESSAGE DO SERUM & URINE PROVIDE?

Common doses of estradiol creams and gels deliver comparable hormone levels to common doses of patches. Serum and urine results for 1.0mg of transdermal cream or gel are approximately equivalent to the highest dose of hormone patches.

WHAT CLINICAL MESSAGE DOES SALIVA PROVIDE?

Estradiol creams and gels deliver far more hormone to cells than hormone patches. At 12 hours after application, saliva results for 1.0mg transdermal cream or gel are more than 10x higher than the highest dose of hormone patches.

This leads us to the big question…

WHICH RESULTS PARALLEL THE CLINICAL PICTURE MORE ACCURATELY?

Are common doses (0.25-1.0mg) of a transdermal estradiol cream or gel supra-physiological (as saliva testing implies) or a relatively modest dose (as serum and urine testing imply)?

This question has been one of intense debate over the past decade, but we have the clinical data to help find the answer.

- The lowest dose of transdermal estradiol gel (0.25mg) did NOT significantly reduce vasomotor symptoms four weeks after beginning therapy but did reduce symptoms after five weeks. A higher dose was effective at all time points.

- The lowest dose of a transdermal estradiol gel did NOT significantly improve bone mineral density six months after beginning therapy, but it did improve after being used for 12 months. A higher dose was effective at six and 12 months. Patches were effective for all doses for both vasomotor symptoms and bone health.

CONCLUSION: While all doses of patches were able to improve bone health and vasomotor symptoms at all doses and time points, transdermal gels required a second level of dosing or longer therapy time to match the clinical effect. This tells us that these “low” doses are likely delivering low hormone levels at the tissue level, as serum and urine results imply. If all tissue in the body were exposed to the amount of hormone that saliva testing implies, (remember 1.0mg elevated levels 10 times higher than a patch) one would expect 0.25mg to be more than enough to match the efficacy of a hormone patch.

Are there any FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) suppression data to support the above conclusion?

Postmenopausal women typically have elevated FSH values. Estrogen therapy will suppress FSH. The more estrogen the brain sees, the more FSH is suppressed.

- Two studies ( Andersson , Pedersen ) showed patches (0.05mg) suppressed FSH 40%, on average.

- Three studies ( Osorio-Wender , Taechakraichana , Callejon ) showed that estradiol gels (1.0-1.5mg) also suppressed FSH 40%, on average.

- If 1.0-1.5mg of transdermal estradiol was truly a monster dose of estradiol (as saliva testing implies), we would expect FSH suppression to exceed that of a patch.

- Transdermal patches of 0.05mg and estradiol gels of 1.0-1.5mg result in similar DUTCH results and similar FSH suppression. Note: One study in each group used progestins, which may suppress FSH additionally.

For me personally, the topic of transdermal hormones has been somewhat of a black box over the past 10 years. My understanding has changed over time and as research has clarified the clinical reality. It is important to know that progesterone behaves somewhat differently, and the above is not entirely representative of transdermal progesterone. While Precision Analytical, Inc. chooses not to take an official position regarding what doses or routes of administration should be used, the data in this post can be helpful in deciding the optimal approach for your patients.

The data also shows that if patients are taking estrogen by transdermal patches, creams, or gels, the resulting concentration shift in the DUTCH test is meaningful and helpful for providers. We encourage providers using these products to monitor estradiol levels, along with the downstream estrogen metabolites, to optimize therapy. We have historically taken a less-confident stance on this scenario because we needed the data to support a particular conclusion. All lab tests (saliva, urine, serum) have HRT-monitoring scenarios where they are not effective for monitoring the appropriate dose of therapy. It is our goal to be your continual source of objective and transparent information on how to best help patients achieve optimal health. For this very popular type of treatment, we are now more confident to endorse using the DUTCH test.

This topic has many different layers to it, and the questions below may help you to further understand.

How do you know that urine levels of estrogen represent the breast and uterus?

In short, we don’t. While the increased hormone levels in saliva following transdermal treatment of estradiol is “real,” the clinical results parallel both serum and urine testing more strongly. If the saliva gland was a critical tissue type, we must admit that serum and urine testing do not offer a good representation of the amount of hormone delivered to this tissue. What about the breast tissue? What about the uterus? These questions, at this point, are answered only with assumptions and require more research. These are also not simple questions. For example, the amount of hormone that gets into the saliva gland depends dramatically on how close to the gland the hormone is applied. This type of information must be carefully considered when we discuss the impact on estrogen-sensitive tissue (breast, etc.) What we do know from the clinical outcomes studied thus far, DUTCH seems to represent the clinical reality well.

Can we learn anything from the elevated salivary values?

Yes! While these values are not useful for monitoring therapy, they do show us that some tissue gets more hormone than is reflected in serum or urine testing. The fallacy of saliva testing is that it is proposed to represent all tissue. This was a reasonable theory (one I used to subscribe to), but the evidence doesn’t support it. We have now seen that for specific situations (bone health, hot flashes, and FSH suppression) this is not true for estradiol. Carefully studying how a man’s LH values respond to transdermal testosterone therapy is another scenario in which serum and urine results seem to parallel the clinical reality much closer than saliva testing. Note : the above does not discount saliva testing’s value as it relates to cortisol testing.

One of the problems with using saliva testing to monitor transdermal products is that the saliva values get much larger if the product is placed on skin close to the saliva gland. When patients use estriol facial creams, salivary estriol will increase exponentially. If patients put their hormone products around the neck, salivary levels will often be much higher than when they are placed further away from the saliva gland (i.e. the thigh). This may be an important lesson when considering where on the body estrogen products should go. If these products are placed on the breast, for example, breast tissues will likely be flooded with hormone. Chang’s study ( 1995, Fertility and Sterility ) showed this very thing when progesterone was applied to the breasts of his female patients. Breast biopsies were done, and levels of tissue progesterone increased about 100-fold. If his hormone application would have been further away (on the thigh, for example) levels would have likely been much lower. Do breast tissue levels of hormones parallel urine or serum values when the product is put on skin that is not near the breast? We do not know the answer to this question as this would require tissue biopsies of multiple areas after progesterone application, but it would be very valuable to know.

The conclusion that 0.25-0.5mg of transdermal estradiol is a low to moderate dose contradicts common experience. Some women use much lower doses (as low as 0.05mg) and feel much better. How can you explain this?

First, we are not taking a position on which doses should be used. A dose lower than 0.25mg may be the best option in some scenarios. We must remember that when the relief of vasomotor symptoms is studied in a proper setting, the placebo group (receiving no estrogen therapy) experiences significant relief. The placebo effect is responsible for about half of the symptom relief according to research. It is also noteworthy that symptom relief took more than 8 weeks to get to its maximum effect.

Because saliva levels offer what might be described as an exaggerated response, the dosing is often lower (as low as 0.05mg) than the typical “low” doses used when serum or urine are the monitoring tool. When some symptom relief (particularly vasomotor symptoms) is reported by the patient with dosing as low as 0.05mg, treatment is assumed to be working. Salivary results often elevate to “normal” premenopausal levels at these very-low doses. This can be misleading, especially in the cases where the placebo effect is somewhat at work.

How should we dose transdermal estrogen in light of this information?

The answer to this question depends on your philosophical approach to HRT and balancing beneficial effects and minimizing risk. The following information details common approaches to HRT:

- No HRT – Some providers fear the increased risks for things like breast cancer and avoid HRT altogether. This approach increased significantly after the WHI study, which showed negative effects from HRT. The synthetic progestins used were responsible for most of the negative outcomes in this study as follow-up research regarding the WHI study has shown.

- Minimal dose for symptom relief – Based on the studies referenced above, doses of estradiol below 1mg may be used to decrease vasomotor symptoms and to help prevent bone loss. A provider with this approach may consider full HRT replacement too risky and without enough additional benefit to justify higher levels. Some providers in this group give hormones long enough to endure vasomotor symptoms during the transition. Others may continue to keep patients on hormones longer for the bone (and other) benefits.

- Full HRT replacement – With this approach, postmenopausal women attempt to return to their premenopausal hormone levels. The thought being that patients were at their prime with young, healthy levels of hormones and some providers wish to return patients as close as possible to this state. The primary concern with this approach is that studies show that risk for breast (and other estrogen-related) cancer is highly related to overall exposure to estrogen (though many other factors are involved as well). There may be concern that cancer risks may be increased with too much estrogen for too long.

The debate about proper HRT dosing gets very confusing. If you, for example, choose full HRT replacement and use saliva testing, your dosing will be much lower than a provider who takes the same approach but uses serum testing (if you use creams and gels). Providers using saliva testing would likely use similar dosing of patches but much lower doses when using creams or gels compared to providers using serum and urine. Many would argue that pushing a woman well into the premenopausal serum and urine range using transdermal creams or gels may result in using uncomfortably high dosing (even more so with progesterone). Some providers using this approach with serum testing have used more than 30mg of estrogen and progesterone >500mg in their transdermal gel/cream.

If your approach is ”minimal dose for symptom relief”, the data seems to point to using doses no higher than 1.0mg of estradiol to begin. Providers may be able to achieve desired results with doses as small as just below 0.25mg, depending on the product. Follow-up testing should show some increase in urine levels. A result between the higher-end of the postmenopausal range, and the bottom part of the premenopausal range, may be a very reasonable approach.

If your position on proper HRT is full replacement, you may want to use higher doses, but be aware that some tissue likely has much more hormone than is represented on a DUTCH or serum test. This may be more hormone than is needed to protect the bone and prevent hot flashes, and there may be increased risks for breast and other estrogen-sensitive cancers. It is even more important in this scenario to ensure that proper phase I metabolism and methylation of estrogens is seen.

How have providers dosed HRT when using saliva testing?

Usually saliva testing results in one of two different approaches:

- Use very small doses and try to keep patients within the premenopausal range. With the exaggerated response of saliva testing and common contamination of samples, this is very challenging and typically leads to estradiol dosing as low as 0.05mg. This approach may lead to a minimal clinical effect although the placebo effect may make it difficult to assess entirely. Providers using this approach would be wise to use other objective measurements to monitor their patients bone density. It is doubtful that these very low doses achieve the type of bone impact that estradiol patches have shown.

- Use common doses of estradiol (0.25-1.0mg) and use a separate “supplementation range” that is much higher than the premenopausal range. This approach may lack clinical validity, but pragmatically it typically results in patients using common doses of transdermal products that have been proven to achieve a significant clinical outcome. I fail to see how this approach would be more effective than simply giving the dose of hormone that makes the most sense (based on the entirety of the clinical picture) and monitoring clinical symptoms and adjusting accordingly. The results of hormone testing should be additive and have the potential to change clinical decisions in a meaningful and legitimate way. One issue with using a “supplementation range” in this scenario is the high variability from one day to the next when the treatment is unchanged (see the last question below for more details).

How does all this information relate to transdermal progesterone creams and gels?

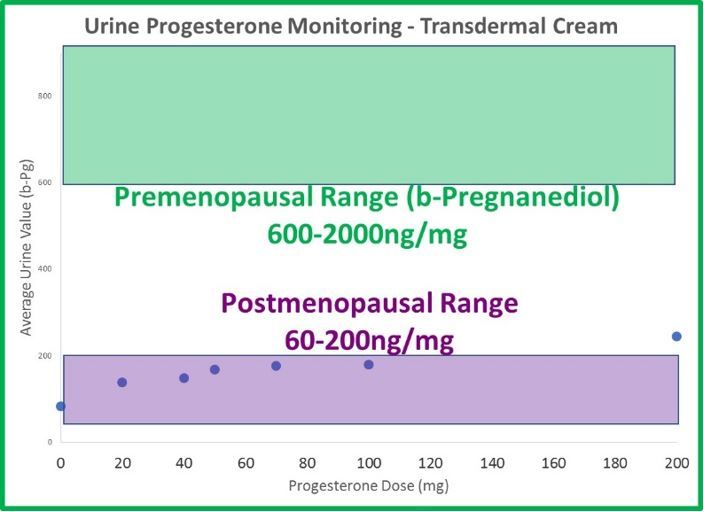

The complexity of monitoring transdermal hormones is borderline irritating. It would be much easier to wrestle through the divergent data from saliva and other tests if the hormones all acted alike, but they do not. Progesterone is much more lipophilic (fat soluble) than estradiol. In the world of topical creams and gels the hormone is often placed over a fatty depot, so it’s not surprising that progesterone behaves differently.

After studying this issue intently for more than a decade now, I am still somewhat unclear about how we should best monitor transdermal progesterone. There may not be a good answer. Here is what we know:

- The odd dichotomy (high saliva, normal serum and urine results) following transdermal estrogen therapy is even more extreme with progesterone. Generally, 20mg is considered a relatively low dose of transdermal progesterone. If given 20mg of transdermal progesterone, the average patient testing saliva 8 hours later has a result 30x higher than an average premenopausal (about 100x higher than postmenopausal) woman. The results are about 8x higher at 12 hours and still more than 4x higher (compared to a premenopausal level) a full 24 hours after application.

- Urine (DUTCH) levels do increase slightly with therapy, but not in a linear fashion, as with estrogen. When patches and cream doses of estradiol increase 3-fold, DUTCH results increase about 3-fold as well. This makes sense. When progesterone doses increase from 20mg to 100mg (500% increase in progesterone), b-pregnanediol (primary metabolite of progesterone) increases only 50%; not 500% as expected. a-Pregnanediol increases slightly more (~80%).

- Salivary results (measured 12 hours after application, ZRT data 2012) increase about 500% when dosing increases from 20mg to 100mg.

- The differences between urine and saliva are staggering when attempting to monitor transdermal progesterone therapy. 100mg leaves urine results below the premenopausal range, and 10mg (maybe less) leaves salivary results well beyond the premenopausal range.

- To date, there is not sufficient evidence that serum, urine or salivary values represent a meaningful clinical result for monitoring transdermal progesterone products. This does not necessarily mean the products do not work clinically. Providers using progesterone transdermally must lean more heavily on the clinical picture. If giving concurrent estrogen therapy, it may be advisable to consider performing endometrial biopsies to ensure the estrogen is adequately opposed.

- Progesterone is much more fat-soluble. There seems to be a depot effect and unexplained migration of hormone. The fact that salivary values sometimes remain very elevated for months after the cessation of therapy, tells us that we have a confusing scenario on our hands. A healthy level of skepticism is a reasonable reaction to the available data.

Conclusion: Transdermal progesterone can be used with success, but lab testing does not presently seem to be helpful in adjusting the dose. There is much more to learn on this front, but we should not assume that any one of the three body fluids available will always accurately represent the clinical reality. Each scenario must be independently validated.

Is bloodspot testing a feasible option for monitoring transdermal therapy?

Bloodspot testing is fascinating in that increased values parallel salivary testing. At any given time, the two do not strongly correlate, but there is a similar pattern. Bloodspot values are wildly variable (as are saliva values) but the two fluctuating values do not increase and decrease together. Bloodspot values are even more prone to contamination (compared to saliva) and this is a very big problem if using this test type. Hormone creams are in concentrations millions of times higher than hormone levels in bloodspot or saliva samples. The smallest amount can throw results way off. When patients use their hands to apply hormones, obtaining a sample from those same fingers is prone to contamination problems. Like saliva testing, bloodspot results help us to understand that some tissue may have more hormone than represented in urine or serum. Bloodspot values correlate reasonably well to serum testing when patients are not on therapy, but serum testing is a better option for monitoring estrogen therapy. In my opinion, bloodspot testing is not a viable option for monitoring HRT effectively when the route of administration is transdermal. Testing capillary blood may be helpful in our future research aimed at more completely understanding the mysteriously elevated salivary results following the use of creams and gels.

Do you have any data that addresses day-to-day variability?

One limitation that providers usually have is that they only get to measure hormones once. They must then assume that the patient’s profile looks reasonably similar from one day to another. One of the things that first turned me off to the prospect of using salivary testing to monitor transdermal progesterone was answering this question. A study was performed in which women used progesterone creams for 14 days and then tested 24 hours after therapy on two back-to-back days. The results showed that the average woman showed a salivary progesterone concentration that changed by 5-fold between the two measurements (unpublished data, used with permission).

To see the variability within one patient, we performed our own informal study. We had a woman collect over 12 days while on 2mg of biestrogen (estradiol and estriol) and 50mg of transdermal progesterone in one compounded product. To allow for an outlier or two, we removed the highest and lowest values (which helped the data more for the saliva than urine) and the results were very encouraging for urine testing. The woman’s urinary estrogen values were all higher than the postmenopausal range. Most were below the premenopausal range and a few snuck into the lower part of the premenopausal range. Estrogen values varied 10-20% (meaning coefficients of variation were 10-20%) and progesterone metabolites varied about 20%. Salivary samples were also collected, and the variation was dramatically higher with progesterone showing results 80% variability. Estradiol results were also highly variable but 1/3 of the results were so high the lab couldn’t provide an actual number (>128, normal range given was 2-9). Some salivary progesterone results were within the premenopausal range while others were 15 times higher. The largest difference was a 40-fold difference between the highest and lowest progesterone values. We certainly don’t want to change therapy based on values that are so different from one day to the next. Estradiol values were all far above the premenopausal range from these 12 days and were also highly variable. When it comes to reproducibility, saliva values are highly problematic for monitoring transdermal products. DUTCH measurements perform much better as it relates to precision.

TAGS

Laboratory Testing: In-Depth Look at DUTCH Urine Testing

Laboratory Testing: In-Depth Look at Saliva Testing

Laboratory Testing: In-Depth Look at Serum Testing

Functional Laboratory Testing: General

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT)

Estrogen and Progesterone

Perimenopausal Women

Premenopausal Women

Postmenopausal Women