What the Media Got Wrong about the WHI

Kaitlin Tyre, ND

What the Media Got Wrong about the WHI

by Kaitlin Tyre, ND

In 2002, published data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), one of the largest and most influential hormone therapy clinical trials to date, inspired media headlines claiming that estrogen and progestin hormone therapy significantly increased the risk of breast cancer, stroke, and blood clots in post-menopausal women. Consequently, a ripple effect of fear and confusion around menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) ensued and negatively impacted the understanding of hormone therapy for years to come.

Thanks to reexamination of the WHI study design, methods, and data, we now know that many of the initial claims and their public representations were quite overblown or misconstrued. In fact, the WHI demonstrated that many risks were lower in MHT users and the risks that did increase were still very rare. While the WHI demonstrated that MHT is safe and beneficial for most women who would typically be prescribed MHT, the belief that it is overall harmful is still common.

Study Background

To set the stage, the WHI was a large scale study organized and funded by the NIH in the 1990s. Hormone therapy was given in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) where women with a uterus were given oral conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) + medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) or placebo, and women without a uterus were given oral CEE alone or placebo. The goal of the HT trial was not to investigate the efficacy of MHT in managing common menopause-related symptoms such as vasomotor symptoms. Its primary objective was to investigate whether oral CEE with or without MPA was an effective preventive intervention for common health concerns such as coronary heart disease (CHD) and osteoporosis-related fractures in postmenopausal women. This objective was created as a response to previous years of observational data demonstrating a net benefit effect of hormone therapy on several health outcomes in postmenopausal women.

To investigate MHT as a preventative therapy, postmenopausal women between the ages of 50 and 79 were recruited for this trial. Of these enrollees, two-thirds of women were above the age of 60 at baseline, and most of the enrollees were 10 or more years past menopause and no longer experiencing menopausal symptoms that would instigate MHT prescribing in the first place. In other words, only one third of the subjects represented the typical MHT patient, which is a woman aged 50-59-years old and within 10 years of menopausal onset.

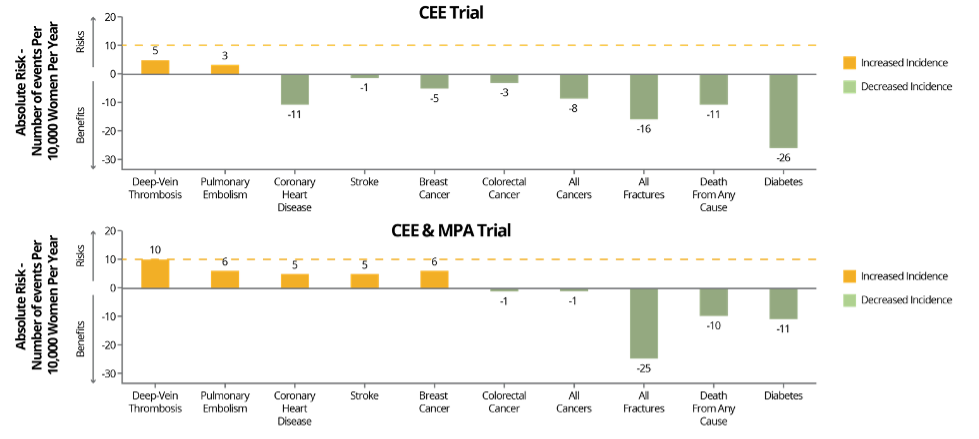

Besides some inherent issues with the trial design, a major weakness of the initial WHI publication release was that the data was presented in terms of relative - not absolute - risk, which, when looking at the numbers, elevates the perception of risk. For example, there was a reported 26% relative risk increase in invasive breast cancer (BC) diagnosis in the CEE + MPA group, and although determined not statistically significant, this increased risk halted the study in its tracks in 2002 due to concerns of further increase. In terms of absolute risk, however, this percentage translates to 8 additional cases of invasive BC per 10,000 person years. For context, less than 10 additional cases per 10,000 person years is considered rare . For further context, this increase in risk is slightly greater than the risk associated with one daily glass of wine but less than that of having two daily glasses of wine. 1 In the 50-59-year-old group, there was an even rarer absolute risk of 6 additional cases per 10,000 person years (see Fig. 1). The 50-59-year-old group represents the more typical MHT patient at least in terms of MHT initiation, which is why this risk stratification is important and relevant. Additionally, twenty year follow-up data from WHI shows that although estrogen and progestin therapy increased the incidence of breast cancer diagnosis , it did not increase mortality from breast cancer. Additionally, estrogen therapy alone resulted in lower invasive BC risk and mortality.

The 2002 results of the combination CEE + MPA trial also showed an increased relative risk of coronary CHD. The CHD risk was initially reported as a 29% increase, which was not only deemed statistically insignificant, but amounted to an absolute risk increase of 7 additional cases per 10,000 person years, which is again, rare, and as seen in Figure 1, was even rarer in the 50-59-year old group. For the typical MHT patient under age 60 and within 10 years of menopause, the rare increase in risk in the CEE + MPA group was determined statistically insignificant and the CEE only trial showed a reduced absolute risk in CHD incidence.

Additionally, a reduction in all-cause mortality was shown in both groups in younger women.

With regards to other cardiovascular related incidents, there was a reported increase in risk of stroke and blood clots or venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the 2002 CEE + MPA data, and the CEE-only trial ultimately ended prematurely in 2004 after 6.8 years of follow up due to a reported increase in incidence of ischemic stroke. The absolute risk increase of stroke in the CEE only trial was an additional 12 cases per 10,000 person years, and the risk of VTE in that trial also increased to an additional 7 cases per 10,000 person years according to the initial data. For the CEE + MPA trial, risk of stroke increased to an additional 8 cases per 10,000 person years and a there was a reported “2-fold increase” from 16 in the placebo group to 34 VTE cases per 10,000 person years. To put into context, this absolute risk of VTE in the CEE + MPA group still amounts to less than the absolute risk of developing a VTE during normal pregnancy. 2 Again, all of these absolute risks were determined to be slightly lower in the 50-59-year age group as seen in Figure 1 below.

Unfortunately, the initial data reporting of these stroke and VTE risks neglected to emphasize the importance of the type of MHT studied in the WHI and how that may play a role in these WHI findings. These risks were extrapolated to all types of MHT when the WHI specifically studied the use of oral estrogen and progestin in women with an intact uterus and oral estrogen in women without a uterus. Future studies would show that transdermal estrogen as opposed to oral estrogen and oral micronized progesterone as opposed to synthetic progestins would have much better safety profiles in terms of stroke and VTE risks. While we should keep cardiovascular risks in mind when prescribing MHT, the newer MHT options may be safer.

Fig. 1: Benefits and risks of the two hormone therapy formulations, conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) alone or in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), evaluated in the Women’s Health Initiative for women aged 50-59 years. Risks and benefits are expressed as the difference in number of events (number of hormone therapy group minus the number in the placebo group) per 10,000 women per year, with <10 per 10,000 per year representing a rare event (dashed red line). Adapted from Manson JE, et al.

Effects on Menopausal Hormone Therapy

There is no question that the WHI MHT study was a landmark trial that helped further the understanding of certain forms of MHT as well as propel other important large studies in the realm of MHT. Unfortunately, the press applied the WHI results to all MHT patients and all hormone therapies. The issues described, combined with the overzealous media response to this high-profile study, significantly altered the recommendation for use of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women and continues to influence decisions around MHT use to this day.

When looking at the WHI, it is crucial to consider the type of hormone therapy used, the age of women included in the study, the number of years since menopause onset, the purpose of MHT use in this particular study, and the differences between statistical concepts like relative risks and absolute risks.

The 2022 North American Menopause Society (NAMS) position paper concludes that while there are these rare risks to consider, MHT is the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms and genitourinary symptoms of menopause and has been shown to help prevent bone loss and fracture. 2 However, and NAMS agrees, like any clinical intervention, the risks and benefits of MHT use must be weighed and the appropriateness of use of MHT must be evaluated individually for each patient.

Summary:

- The WHI looked specifically at the the use of oral conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) as their MHT intervention.

- The WHI study groups included mostly women past the typical age and state of menopause to initiate MHT.

- The increased risk of invasive BC diagnosis found in the CEE + MPA trial is considered rare although it was publicized with headlines suggesting it was a big risk.

- There are MHT options that may have better safety profiles with regards to stroke and blood clot risks.

- Many of the rare increased risks are even rarer in women in the 50-59-year age group when MHT is typically initiated for menopause related symptoms such as VMS and GSM.

- There were several reported risk reductions in both CEE + MPA and CEE trials, including a reduction in hip fractures, and in the 50-59-year age group there was a decreased risk in terms of all cause mortality and diabetes among others as seen in Figure 1.

- MHT is the most effective treatment for menopause related VMS and GSM.

- Appropriateness of MHT should be individually assessed and treatment individualized to every patient for best outcomes.

Become a DUTCH Provider to gain access to expert clinical support and education, comprehensive reports, and peer-reviewed and validated research.

References

- Faubion SS, Crandall CJ, Davis L, et al. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause . 2022;29(7):767-794. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

- Lobo RA. Where are we 10 years after the women’s health initiative? Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism . 2013;98(5):1771-1780. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-4070

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: Principal results from the women’s health initiative randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association . 2002;288(3):321-333. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321

- Committee* TWHIS. Effects of Conjugated Equine Estrogen in Postmenopausal Women With HysterectomyThe Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA . 2004;291(14):1701-1712. doi:10.1001/jama.291.14.1701

- Pedersen AT, Ottesen B. Issues to debate on the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study. Epidemiology or randomized clinical trials - Time out for hormone replacement therapy studies? Human Reproduction . 2003;18(11):2241-2244. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg435

- Cagnacci A, Venier M. The controversial history of hormone replacement therapy. Medicina (Lithuania) . 2019;55(9). doi:10.3390/medicina55090602

- A critique of Women’s Health Initiative Studies (2002-2006). Nuclear Receptor Signaling . 2007;4. doi:10.1621/nrs.04023

- Manson JAE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the women’s health initiative randomized trials. JAMA . 2013;310(13):1353-1368. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278040

- Stute P, Marsden J, Salih N, Cagnacci A. Reappraising 21 years of the WHI study: Putting the findings in context for clinical practice. Maturitas . 2023;174:8-13. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2023.04.271

TAGS

Postmenopausal Women

Estrogen and Progesterone

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT)

Menopause