DUTCH Fest 2026 is sold out! Join the list to get notified about our next DUTCH Fest.

Menopause & Stress

Hilary Miller, ND

Menopause & Stress

by Hilary Miller, ND

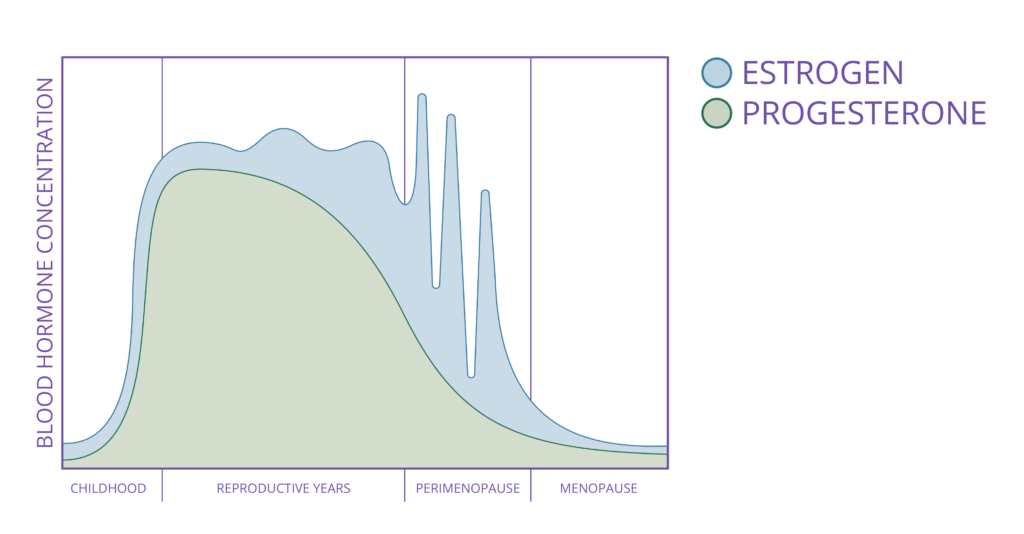

Menopause marks a new stage in life when ovaries stop producing estrogen and progesterone in a monthly cycle, resulting in a dramatic decline in both hormones. For 2-8 years before the final menstrual period, average hormone levels of progesterone and estrogen shift. This phase is called perimenopause. Since both hormones impact many body systems, such as bones, the nervous system, the cardiovascular system, metabolism, and the stress response, many women experience a change in quality of life, sleep, mental health, weight management, and stress during this time. 1

Below is a representation of estradiol and progesterone levels throughout a woman’s lifetime. Note that before menopause there are several years of decline in average progesterone with erratic fluctuations in average estradiol levels. After perimenopause, estradiol and progesterone levels are low.

Stress presents an added challenge to menopause. Stress comes in many forms and can impact the body in conflicting ways, depending on the woman’s unique history and response.

What is Stress?

Stress can be physical, such as exercise, work, or play. It can be emotional, such as a reaction to a high workload 2 or a perceived negative interaction with a friend. Stress can be short-term, such as with a minor car accident or an amusement park ride. Stress can be long-term when there is a major life change like a move or a death in the family. How stress is perceived varies from person to person, but a core component of stress is a hormone: Cortisol.

Cortisol is one of several hormones that are produced by the adrenal glands. It is a powerful cell-signaling hormone that increases blood sugar, improves insulin sensitivity, reduces growth hormone and active thyroid hormone (T3), suppresses immune reactivity and inflammation, and mobilizes fats and proteins for use as energy and building blocks. 3 In short, cortisol has a powerful impact on how the body functions. The body uses cortisol as a key component of the awakening response, bringing the body into metabolic activation and focus after sleep. But this powerful kick-start must be short-lived to promote optimal wellness. Because of its numerous effects on metabolism and inflammation, cortisol needs to stay at modest levels unless specific stressors occur to allow proper immune and metabolic functioning during stress.

The cortisol response is controlled by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. This axis begins in two closely connected structures in the brain, the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland. In the form of nerve impulses such as pain or fear, stress triggers the release of catecholamines and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH binds receptors in the adrenal cortex in two specific areas, the zona fasiculata (cortisol release) and the zona reticularis (DHEA release).

Good stress, such as exercise, utilizes cortisol to promote increased energy availability and focus. Good stress is short-lived, and cortisol levels decline after the stress allowing the return of immune function and rest. Bad stress, such as a heavy mental load from work or personal events, continues indefinitely, perhaps for days, weeks, or months. Cortisol increases to promote optimal focus on the problem, but with bad stress the problem is persistent beyond what is healthy. Cortisol subsequently chronically raises baseline blood sugar and suppresses beneficial immune function.

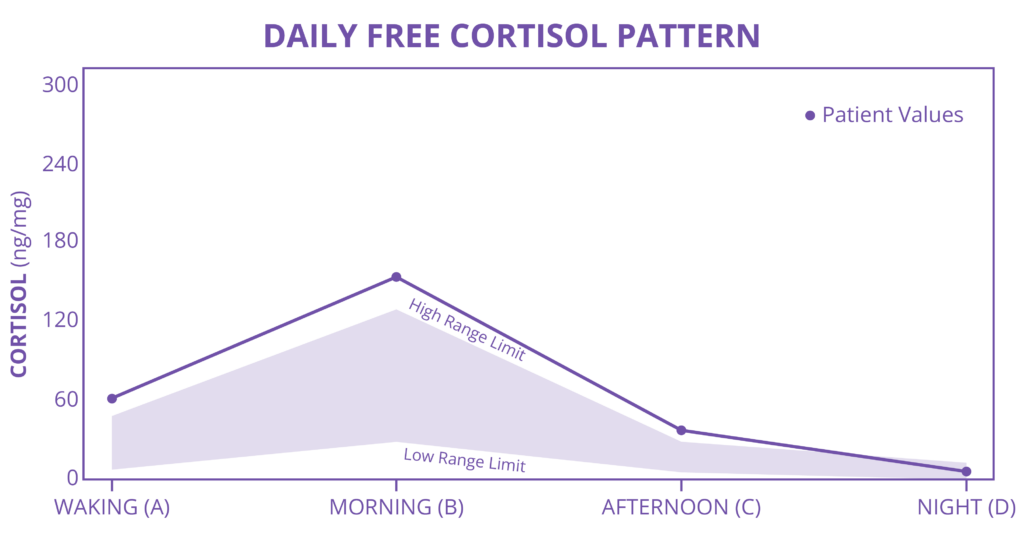

Example of excess cortisol of acute stress

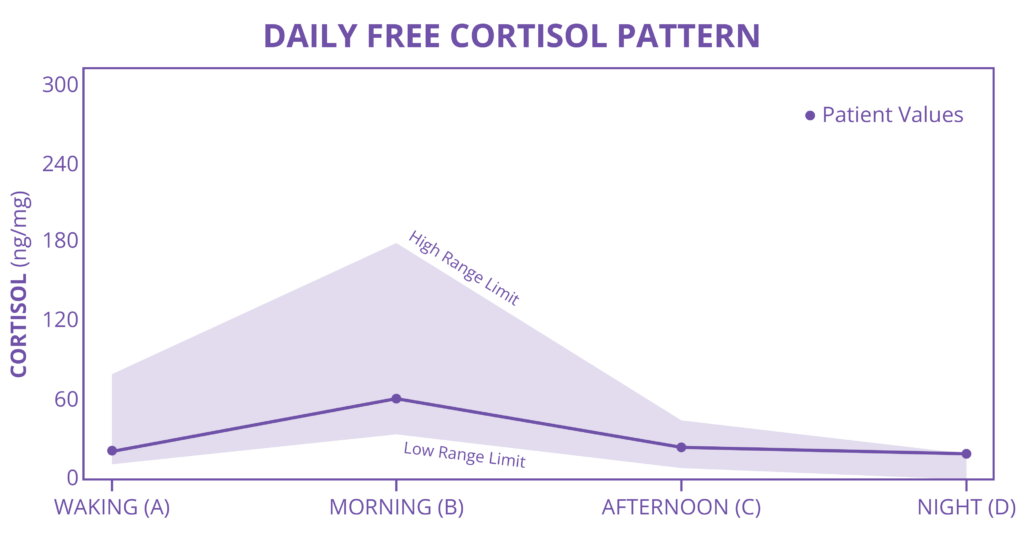

After a period of increased stress activation and cortisol, the body has smart mechanisms for preventing excess damage from chronic cortisol exposure: Cortisol deactivation and HPA axis impairment. Either on a cellular level, active cortisol is “turned off” by being converted into cortisone, or on a systemic level, the signal to release cortisol is blunted even during perceived stress, simultaneously blunting DHEA (the major source of androgens for women and estrogens in postmenopausal women). 4

Another way that stress can impact cortisol is through circadian rhythm disruption. The circadian rhythm of cortisol includes a peak in the morning followed by a decline, with only tiny amounts of cortisol made at night. Circadian rhythm disruption can lead to many issues: poor cortisol in the morning, and high cortisol at night. In some cases, overall cortisol output is normal but the expected curve is flattened. With a flattened curve, even though total daily cortisol can be normal, both the lack of a sharp rise in cortisol on waking AND the lack of a “break” from cortisol at night can lead to weight gain, metabolic disease, poor immune function, depression, and a host of other health issues. 5

Example of blunted cortisol circadian rhythm, low DHEA with chronic stress

Menopause and stress

Stress can significantly impact menopause in several ways:

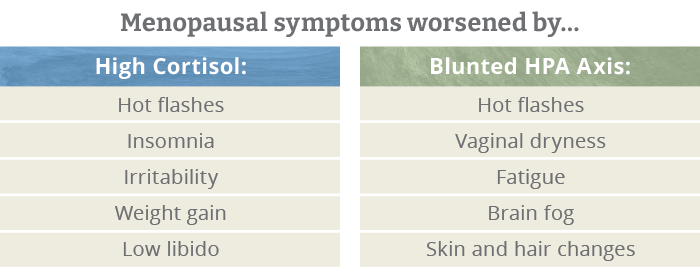

- Hormone imbalance : Chronic stress can lead to blunted HPA axis and DHEA, and even lower hormones than typical in menopause.

- Menopausal symptoms : Stress can intensify hot flashes, mood swings, and insomnia. Women with high stress levels can find their symptoms are more severe and persistent.

- Bone health: The decline in estradiol in menopause increases the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. High cortisol can also reduce bone mineral density, further increasing this risk.

- Cardiovascular health : Estrogen is cardioprotective and its decline in menopause increases cardiovascular disease risk. High cortisol from stress can further increase this risk by increasing blood pressure, inflammation, and other factors associated with heart disease.

- Emotional health: Mood swings, anxiety, and depression are common menopausal complaints. Stress worsens mental health conditions and makes mood swings less predictable.

Symptoms of menopause, even years before the FMP, can be worsened with higher levels of cortisol. Conversely, low cortisol of chronic stress has its own challenges. As mentioned above, persistent and prolonged stress and high cortisol can blunt ACTH output. This not only reduces available cortisol, contributing to fatigue and poor energy availability, but it reduces DHEA , the body’s main hormone source after menopause. Menopausal women who have a blunted HPA axis can have abnormally low DHEA, and subsequently, estrogen. Since she will already be going through a significant decline in estrogen, this can make the transition even harder.

Addressing Stress and Menopause

The best time to address stress is before menopause, but addressing it at any point in the journey helps.

Many providers focus on sex hormone measurement for menopausal complaints, but the adrenal panel on the DUTCH test is equally important. Cortisol and its impact on perimenopause and menopause can be measured. The DUTCH test has specialized in comprehensive sex and adrenal hormone measurement for over a decade, and both the DUTCH Plus and the DUTCH Complete tests are great choices.

The best strategy depends on the hormone levels and the patient’s history. The following is a short list of strategies that have demonstrated benefits for the HPA axis and stress perception.

- Yoga and Meditation 6 can improve cortisol responses and self-reported experiences of stress.

- Journaling about goals 7 can improve a blunted HPA axis and recover from chronic stress.

- B-vitamin supplementation 8 can improve circadian rhythms and waking cortisol.

- Herb/Mushroom adaptogens 9-12 can support balanced cortisol levels. If cortisol is low, adaptogens can increase its output, which may simultaneously increase adrenal DHEA output.

- Estrogen replacement therapy 13 may limit the increase in cortisol output seen in menopausal women.

- DHEA supplementation 14 can improve some of the hormone imbalance symptoms seen with menopause, if DHEA is low on testing.

Conclusion

The impact of emotional and physical stress on menopause is complex. Understanding the role of adrenal function in perimenopause and menopause can improve treatment outcomes dramatically. Although DUTCH suggests looking at the HPA axis with every stage of life, menopause presents special challenges that can and should be understood by both patients and providers alike. By assessing and addressing the HPA axis through lifestyle, supplements, and possibly HRT, hormonal changes can be more easily navigated.

Become a DUTCH Provider to learn more about how comprehensive adrenal and sex hormone testing can help you create informed patient treatment plans.

References

1. NAMS. Menopause Practice: A Clinicians Guide. 6th ed. Crandall CJ, editor. Pepper Pike, Ohio: North American Menopause Society; 2019. 364 p.

2. Wolfram M, et al. Emotional exhaustion and overcommitment to work are differentially associated with hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis responses to a low-dose ACTH<sub>1–24</sub>(Synacthen) and dexamethasone–CRH test in healthy school teachers. Stress. 2013;16(1):54-64.

3. Guilliams T. The Role of Stress and the HPA Axis in Chronic Disease Management: Principles and Protocols for Healthcare Professionals. Second ed. Stevens Point, WI: Pointe Institute; 2020. 167 p.

4. Labrie F, et al. DHEA and its transformation into androgens and estrogens in peripheral target tissues: intracrinology. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2001;22(3):185-212.

5. Al-Safi ZA, et al. Evidence for disruption of normal circadian cortisol rhythm in women with obesity. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2018;34(4):336-340.

6. Cahn BR, et al. Yoga, Meditation and Mind-Body Health: Increased BDNF, Cortisol Awakening Response, and Altered Inflammatory Marker Expression after a 3-Month Yoga and Meditation Retreat. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:315.

7. Teismann T, et al. Writing about life goals: effects on rumination, mood and the cortisol awakening response. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(11):1410-1419.

8. Camfield DA, et al. The effects of multivitamin supplementation on diurnal cortisol secretion and perceived stress. Nutrients. 2013;5(11):4429-4450.

9. Panossian A, Wikman G. Effects of Adaptogens on the Central Nervous System and the Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Their Stress-Protective Activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2010;3(1):188-224.

10. Anghelescu I-G, et al. Stress management and the role of Rhodiola rosea : a review. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2018;22(4):242-252.

11. Zhang DW, et al. The effects of Cordyceps sinensis phytoestrogen on estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:484.

12. Cheah KL, et al. Effect of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extract on sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0257843.

13. Weiser MJ, Handa RJ. Estrogen impairs glucocorticoid dependent negative feedback on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis via estrogen receptor alpha within the hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2009;159(2):883-895.

14. Climara (Estradiol Transdermal System) [package insert]. Wayne, NJ. Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Inc., 2007.

TAGS

Women's Health

Postmenopausal Women

Stress

Cortisol

Menopause

Obesity

Sleep